BY: RENEE CHO

View the original article here

Green hydrogen has been in the news often lately. President-elect Biden has promised to use renewable energy to produce green hydrogen that costs less than natural gas. The Department of Energy is putting up to $100 million into the research and development of hydrogen and fuel cells. The European Union will invest $430 billion in green hydrogen by 2030 to help achieve the goals of its Green Deal. And Chile, Japan, Germany, Saudi Arabia, and Australia are all making major investments into green hydrogen.

So, what is green hydrogen? Simply put, it is hydrogen fuel that is created using renewable energy instead of fossil fuels. It has the potential to provide clean power for manufacturing, transportation, and more — and its only byproduct is water.

Where does green hydrogen come from?

Hydrogen energy is very versatile, as it can be used in gas or liquid form, be converted into electricity or fuel, and there are many ways of producing it. Approximately 70 million metric tons of hydrogen are already produced globally every year for use in oil refining, ammonia production, steel manufacturing, chemical and fertilizer production, food processing, metallurgy, and more.

There is more hydrogen in the universe than any other element—it’s been estimated that approximately 90 percent of all atoms are hydrogen. But hydrogen atoms do not exist in nature by themselves. To produce hydrogen, its atoms need to be decoupled from other elements with which they occur— in water, plants or fossil fuels. How this decoupling is done determines hydrogen energy’s sustainability.

Most of the hydrogen currently in use is produced through a process called steam methane reforming, which uses a catalyst to react methane and high temperature steam, resulting in hydrogen, carbon monoxide and a small amount of carbon dioxide. In a subsequent process, the carbon monoxide, steam and a catalyst react to produce more hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Finally the carbon dioxide and impurities are removed, leaving pure hydrogen. Other fossil fuels, such as propane, gasoline, and coal can also be used in steam reforming to produce hydrogen. This method of production—powered by fossil fuels—results in gray hydrogen as well as 830 million metric tons of CO2 emissions each year, equal to the emissions of the United Kingdom and Indonesia combined.

When the CO2 produced from the steam methane reforming process is captured and stored elsewhere, the hydrogen produced is called blue hydrogen.

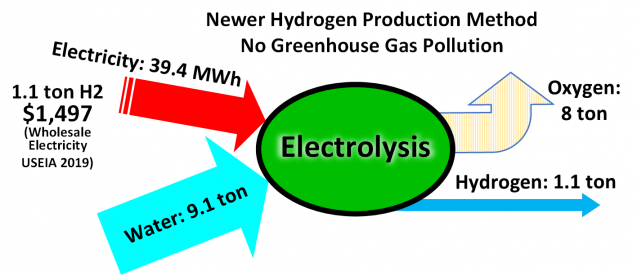

Hydrogen can also be produced through the electrolysis of water, leaving nothing but oxygen as a byproduct. Electrolysis employs an electric current to split water into hydrogen and oxygen in an electrolyzer. If the electricity is produced by renewable power, such as solar or wind, the resulting pollutant-free hydrogen is called green hydrogen. The rapidly declining cost of renewable energy is one reason for the growing interest in green hydrogen.

Why green hydrogen is needed

Most experts agree that green hydrogen will be essential to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, since there are certain portions of the economy whose emissions are difficult to eliminate. In the U.S., the top three sources of climate-warming emissions come from transportation, electricity generation and industry.

Energy efficiency, renewable power, and direct electrification can reduce emissions from electricity production and a portion of transportation; but the last 15 percent or so of the economy, comprising aviation, shipping, long-distance trucking and concrete and steel manufacturing, is difficult to decarbonize because these sectors require high energy density fuel or intense heat. Green hydrogen could meet these needs.

Advantages of green hydrogen

Hydrogen is abundant and its supply is virtually limitless. It can be used where it is produced or transported elsewhere. Unlike batteries that are unable to store large quantities of electricity for extended periods of time, hydrogen can be produced from excess renewable energy and stored in large amounts for a long time. Pound for pound, hydrogen contains almost three times as much energy as fossil fuels, so less of it is needed to do any work. And a particular advantage of green hydrogen is that it can be produced wherever there is water and electricity to generate more electricity or heat.

Hydrogen has many uses. Green hydrogen can be used in industry and can be stored in existing gas pipelines to power household appliances. It can transport renewable energy when converted into a carrier such as ammonia, a zero-carbon fuel for shipping, for example.

Hydrogen can also be used with fuel cells to power anything that uses electricity, such as electric vehicles and electronic devices. And unlike batteries, hydrogen fuel cells don’t need to be recharged and won’t run down, so long as they have hydrogen fuel.

Fuel cells work like batteries: hydrogen is fed to the anode, oxygen is fed to the cathode; they are separated by a catalyst and an electrolyte membrane that only allows positively charged protons through to the cathode. The catalyst splits off the hydrogen’s negatively charged electrons, allowing the positively charged protons to pass through the electrolyte to the cathode. The electrons, meanwhile, travel via an external circuit—creating electricity that can be put to work—to meet the protons at the cathode, where they react with the oxygen to form water.

Hydrogen is used to power hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Because of its energy efficiency, a hydrogen fuel cell is two to three times more efficient than an internal combustion engine fueled by gas. And a fuel cell electric vehicle’s refueling time averages less than four minutes.

Because they can function independently from the grid, fuel cells can be used in the military field or in disaster zones and work as independent generators of electricity or heat. When fixed in place they can be connected to the grid to generate consistent reliable power.

The challenges of green hydrogen

Its flammability and its lightness mean that hydrogen, like other fuels, needs to be properly handled. Many fuels are flammable. Compared to gasoline, natural gas, and propane, hydrogen is more flammable in the air. However, low concentrations of hydrogen have similar flammability potential as other fuels. Since hydrogen is so light—about 57 times lighter than gasoline fumes—it can quickly disperse into the atmosphere, which is a positive safety feature.

Because hydrogen is so much less dense than gasoline, it is difficult to transport. It either needs to be cooled to -253˚C to liquefy it, or it needs to be compressed to 700 times atmospheric pressure so it can be delivered as a compressed gas. Currently, hydrogen is transported through dedicated pipelines, in low-temperature liquid tanker trucks, in tube trailers that carry gaseous hydrogen, or by rail or barge.

Today 1,600 miles of hydrogen pipelines deliver gaseous hydrogen around the U.S., mainly in areas where hydrogen is used in chemical plants and refineries, but that is not enough infrastructure to accommodate widespread use of hydrogen.

Natural gas pipelines are sometimes used to transport only a limited amount of hydrogen because hydrogen can make steel pipes and welds brittle, causing cracks. When less than 5 to 10 percent of it is blended with the natural gas, hydrogen can be safely distributed via the natural gas infrastructure. To distribute pure hydrogen, natural gas pipelines would require major alterations to avoid potential embrittlement of the metal pipes, or completely separate hydrogen pipelines would need to be constructed.

Fuel cell technology has been constrained by the high cost of fuel cells because platinum, which is expensive, is used at the anode and cathode as a catalyst to split hydrogen. Research is ongoing to improve the performance of fuel cells and to find more efficient and less costly materials.

A challenge for fuel cell electric vehicles has been how to store enough hydrogen—five to 13 kilograms of compressed hydrogen gas—in the vehicle to achieve the conventional driving range of 300 miles.

The fuel cell electric vehicle market has also been hampered by the scarcity of refueling stations. As of August, there were only 46 hydrogen fueling stations in the U.S., 43 of them in California; and hydrogen costs about $8 per pound, compared to $3.18 for a gallon of gas in California.

It all comes down to cost

The various obstacles green hydrogen faces can actually be reduced to just one: cost. Julio Friedmann, senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, believes the only real challenge of green hydrogen is its price. The fact that 70 million tons of hydrogen are produced every year and that it is shipped in pipelines around the U.S. shows that the technical issues of distributing and using hydrogen are “straightforward, and reasonably well understood,” he said.

The problem is that green hydrogen currently costs three times as much as natural gas in the U.S. And producing green hydrogen is much more expensive than producing gray or blue hydrogen because electrolysis is expensive, although prices of electrolyzers are coming down as manufacturing scales up. Currently, gray hydrogen costs about €1.50 euros ($1.84 USD) per kilogram, blue costs €2 to €3 per kilogram, and green costs €3.50 to €6 per kilogram, according to a recent study.

Friedmann detailed three strategies that are key to bringing down the price of green hydrogen so that more people will buy it:

- Support for innovation into novel hydrogen production and use. He noted that the stimulus bill Congress just passed providing this support will help cut the cost of fuel cells and green hydrogen production in years to come.

- Price supports for hydrogen, such as an investment tax credit or production tax credit similar to those established for wind and solar that helped drive their prices down.

- A regulatory standard to limit emissions. For example, half the ammonia used today goes into fertilizer production. “If we said, ‘we have an emission standard for low carbon ammonia,’ then people would start using low carbon hydrogen to make ammonia, which they’re not today, because it costs more,” said Friedmann. “But if you have a regulation that says you have to, then it makes it easier to do.” Another regulatory option is that the government could decide to procure green hydrogen and require all military fuels to be made with a certain percentage of green hydrogen.

Green hydrogen’s future

A McKinsey study estimated that by 2030, the U.S. hydrogen economy could generate $140 billion and support 700,000 jobs.

Friedmann believes there will be substantial use of green hydrogen over the next five to ten years, especially in Europe and Japan. However, he thinks the limits of the existing infrastructure will be reached very quickly—both pipeline infrastructure as well as transmission lines, because making green hydrogen will require about 300 percent more electricity capacity than we now have. “We will hit limits of manufacturing of electrolyzers, of electricity infrastructure, of ports’ ability to make and ship the stuff, of the speed at which we could retrofit industries,” he said. “We don’t have the human capital, and we don’t have the infrastructure. It’ll take a while to do these things.”

Many experts predict it will be 10 years before we see widespread green hydrogen adoption; Friedmann, however, maintains that this 10-year projection is based on a number of assumptions. “It’s premised on mass manufacturing of electrolyzers, which has not happened anywhere in the world,” he said. “It’s premised on a bunch of policy changes that have not been made that would support the markets. It’s premised on a set of infrastructure changes that are driven by those markets.”

There are a number of green energy projects in the U.S. and around the world attempting to address these challenges and promote hydrogen adoption. Here are a few examples.

California will invest $230 million on hydrogen projects before 2023; and the world’s largest green hydrogen project is being built in Lancaster, CA by energy company SGH2. This innovative plant will use waste gasification, combusting 42,000 tons of recycled paper waste annually to produce green hydrogen. Because it does not use electrolysis and renewable energy, its hydrogen will be cost-competitive with gray hydrogen.

A new Western States Hydrogen Alliance, made up of leaders in the heavy-duty hydrogen and fuel cell industry, are pushing to develop and deploy fuel cell technology and infrastructure in 13 western states.

Hydrogen Europe Industry, a leading association promoting hydrogen, is developing a process to produce pure hydrogen from the gasification of biomass from crop and forest residue. Because biomass absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as it grows, the association maintains that it produces relatively few net carbon emissions.

Breakthrough Energy, co-founded by Bill Gates, is investing in a new green hydrogen research and development venture called the European Green Hydrogen Acceleration Center. It aims to close the price gap between current fossil fuel technologies and green hydrogen. Breakthrough Energy has also invested in ZeroAvia, a company developing hydrogen-fueled aviation.

In December, the U.N. launched the Green Hydrogen Catapult Initiative, bringing together seven of the biggest global green hydrogen project developers with the goal of cutting the cost of green hydrogen to below $2 per kilogram and increasing the production of green hydrogen 50-fold by 2027.

Ultimately, whether or not green hydrogen fulfills its promise and potential depends on how much carmakers, fueling station developers, energy companies, and governments are willing to invest in it over the next number of years.

But because doing nothing about global warming is not an option, green hydrogen has a great deal of potential, and Friedmann is optimistic about its future. “Green hydrogen is exciting,” he said. “It’s exciting because we can use it in every sector. It’s exciting because it tackles the hardest parts of the problem—industry and heavy transportation. It’s interesting, because the costs are coming down. And there’s lots of ways to make zero-carbon hydrogen, blue and green. We can even make negative carbon hydrogen with biohydrogen. Twenty years ago, we didn’t really have the technology or the wherewithal to do it. And now we do.”