Data centers, factories, heat pumps and EVs are putting increasing stress on a grid that isn’t growing fast enough, new data shows.

Written by: Jeff St. John

View the original article here

For the past two decades, demand for electricity across the United States has hardly increased. But those dynamics appear to have dramatically reversed — and U.S. electric utilities, regulators and power grid planners aren’t prepared to deal with this new paradigm of surging electricity demand.

That’s the key takeaway from a new report by consultancy Grid Strategies called The Era of Flat Power Demand Is Over. Already, massive amounts of clean energy projects are stuck waiting for grid expansions to happen so they can connect. Soon enough, data centers, factories, electric-vehicle charging depots and other major electricity users could start facing the same barriers, the report warns.

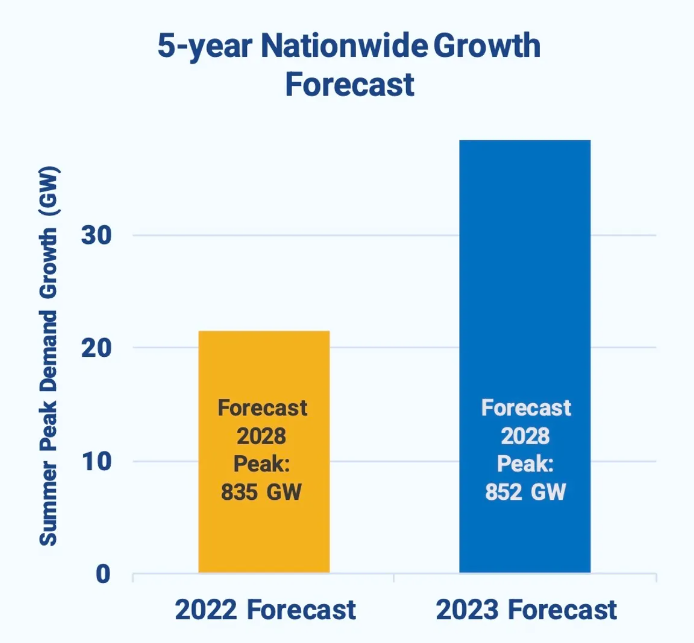

In the past year, estimates from U.S. utilities and grid operators of how much electricity demand will grow over the next five years have nearly doubled, jumping from 2.6 percent to 4.7 percent, according to Grid Strategies’ analysis. That’s far higher than the more incremental 0.5 percent annual demand growth estimates of the past decade.

Over the past 20 years, efficiency improvements — primarily replacing incandescent lightbulbs with fluorescents and then LEDs — have counterbalanced rising power demand from population and economic growth, giving utilities and regulators little reason to expand their power grids or generation capacity.

“I think people got used to…flat power demand,” said Rob Gramlich, Grid Strategies president.

But the combination of near-term growth in electricity use by data centers and industry and longer-term growth from electric vehicles and building heating has upended that status quo, he said. “Those who are actively involved in electrifying parts of the economy understand that that means more electricity demand. But it’s only been dribbling out anecdotally here and there.”

That anecdotal data has piled up. In Virginia’s Loudoun County, dubbed “Data Center Alley” for its remarkably high concentration of data centers, power shortfalls have prompted utility Dominion Energy to push grid planners to approve a multibillion-dollar grid expansion; some data center operators and regulators have even proposed running backup diesel generators to cover power gaps. In California, lags in grid expansions are causing monthslong wait times for getting connected to utility service, not just for major new loads like electric truck-charging depots but even for everyday commercial and multifamily buildings.

All told, grid planners across the U.S. forecast an increase of 38 gigawatts of peak demand by 2028, according to data reported to federal regulators — a pace of growth that will be hard to keep up with. Data centers and factories can be built in a few years, but it takes four years or more to build new power plants, and up to a decade or longer to build new transmission lines.

While this is a problem that goes beyond the clean energy sector, it also presents a particular hurdle for the energy transition. Not only does the U.S. need to rapidly replace existing coal- and gas-fired power plants with renewables — it also needs to grow fast enough to accommodate the surge of new electricity demand. For this new demand to be met in a way that doesn’t derail the transition away from fossil fuels, the U.S. will need to clear the way for a much speedier buildout of wind, solar, batteries and power lines.

“The main reason [tracking increases in electricity demand] is important is for infrastructure planning,” Gramlich said. “Transmission infrastructure in particular takes a long time. As soon as we know this load situation to be the case, we’d better act quickly.”

A sector-by-sector breakdown of where new electricity demand is coming from

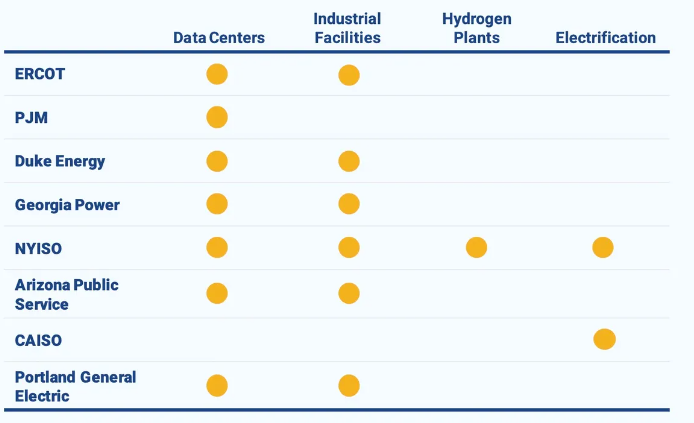

Grid Strategies highlighted key demand-growth drivers across several major grid regions, including PJM, which operates the grid in all or part of 13 states from Illinois to Virginia, as well as the grid operators for California, New York and Texas, and four large utilities: Arizona Public Service, Duke Energy, Georgia Power and Portland General Electric in Oregon.

Data centers and industrial facilities were among the biggest drivers of new load. New investments in U.S. data centers are projected to exceed $150 billion through 2028, driven by rising demand for cloud computing, telecommunications, digitization and artificial intelligence. Data centers already make up roughly 2.5 percent of total U.S. electricity demand, according to analysis from Boston Consulting Group — but exploding demand for AI could drive that to 7.5 percent by 2030.

New industrial facilities are also adding demands on the grid. The country has seen about $481 billion in commitments to build and expand industrial and manufacturing facilities since 2021, the report states. Much of that growth stems from the clean energy manufacturing boom and is concentrated in the Midwest and Southeast, which are receiving the lion’s share of battery and EV manufacturing investments spurred by the tens of billions of dollars of federal incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act.

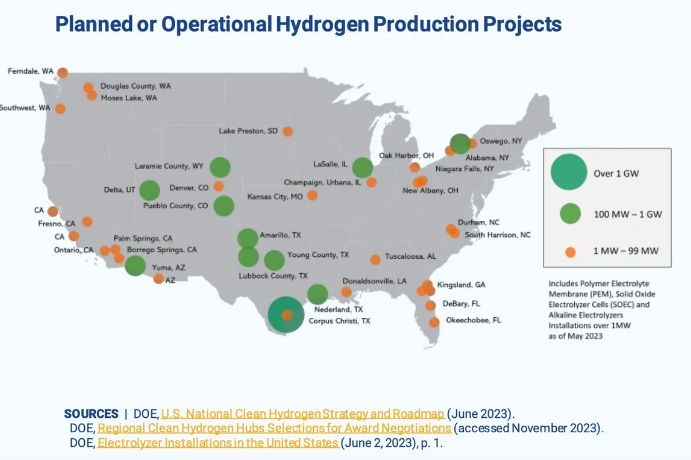

Not all of the emerging demands for grid electricity are fully accounted for in current load-growth forecasts, Gramlich noted. One striking example is hydrogen produced from zero-carbon electricity, supported by lucrative tax credits offered by the Inflation Reduction Act, which could add gigawatts’ worth of new power demand across the country. But with the exception of New York, grid planners’ “load forecasts don’t appear to be explicitly considering the implications of hydrogen fuel plants,” according to the repo

Increased electricity demand stemming from the electrification of transportation and buildings — a key facet of the Biden administration’s climate plans — is not as granularly tracked in states outside those with aggressive policies on those fronts, such as those adopted by California and New York. In California, where policymakers have set their sights on replacing fossil-fueled vehicles and building heating systems with EVs and heat pumps, respectively, statewide electricity demand is expected to grow by about 60 percent through 2045, according to an analysis from utility Southern California Edison — a remarkable turnaround from a state that’s led the country on energy efficiency. New York expects similar increases in electricity demand over the coming decades.

How uncertainty and cost concerns have limited grid infrastructure buildout

Though it’s clear what direction power demand is moving in, “we don’t know enough yet to say what load growth is going to be,” Gramlich cautioned. Load forecasting is an inherently uncertain field. Some proposed data centers and factories may never be built. The uptake rates of EVs or electric-powered heat pumps for homes and buildings can’t be predicted with perfect accuracy.

These uncertainties can lead utility regulators to look askance at utility grid-expansion proposals that may exceed future needs, since their costs are passed on to utility customers via increases on their bills. Over the past half-decade or so, a number of large-scale utility grid-expansion plans have been denied by state regulators due to concerns over excessive costs.

Similar dynamics have slowed efforts within the independent system operators and regional transmission organizations that manage the grids that provide electricity to roughly two-thirds of the country’s population. Since a series of large-scale buildouts in the early 2010s, the scale of U.S. grid projects has declined significantly, with the average miles of newly built high-voltage transmission lines falling by more than half from the first half to the second half of that decade.

Several of these grid operators have approved multibillion-dollar grid buildout plans in the past two years. But those plans still tend to project lower levels of load growth than the data in Grid Strategies’ study indicates is on its way, Gramlich said. “It may be that everybody’s base case needs to be ratcheted up.”

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which regulates interstate transmission policy, is in the midst of crafting proposed transmission rules that are expected to require grid operators and utilities to examine a broader set of future grid needs, including increasing demand from electrification of transport and buildings, when making their long-term grid plans.

“There should be a lot of work coming up for every region following the FERC rule,” which is expected some time in the first half of 2024, Gramlich said. “That rule will require a lot of planning — and the devil’s in the details in every region.

New industrial facilities are also adding demands on the grid. The country has seen about $481 billion in commitments to build and expand industrial and manufacturing facilities since 2021, the report states. Much of that growth stems from the clean energy manufacturing boom and is concentrated in the Midwest and Southeast, which are receiving the lion’s share of battery and EV manufacturing investments spurred by the tens of billions of dollars of federal incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act.

Not all of the emerging demands for grid electricity are fully accounted for in current load-growth forecasts, Gramlich noted. One striking example is hydrogen produced from zero-carbon electricity, supported by lucrative tax credits offered by the Inflation Reduction Act, which could add gigawatts’ worth of new power demand across the country. But with the exception of New York, grid planners’ “load forecasts don’t appear to be explicitly considering the implications of hydrogen fuel plants,” according to the report.

Increased electricity demand stemming from the electrification of transportation and buildings — a key facet of the Biden administration’s climate plans — is not as granularly tracked in states outside those with aggressive policies on those fronts, such as those adopted by California and New York. In California, where policymakers have set their sights on replacing fossil-fueled vehicles and building heating systems with EVs and heat pumps, respectively, statewide electricity demand is expected to grow by about 60 percent through 2045, according to an analysis from utility Southern California Edison — a remarkable turnaround from a state that’s led the country on energy efficiency. New York expects similar increases in electricity demand over the coming decades.

How uncertainty and cost concerns have limited grid infrastructure buildout

Though it’s clear what direction power demand is moving in, “we don’t know enough yet to say what load growth is going to be,” Gramlich cautioned. Load forecasting is an inherently uncertain field. Some proposed data centers and factories may never be built. The uptake rates of EVs or electric-powered heat pumps for homes and buildings can’t be predicted with perfect accuracy.

These uncertainties can lead utility regulators to look askance at utility grid-expansion proposals that may exceed future needs, since their costs are passed on to utility customers via increases on their bills. Over the past half-decade or so, a number of large-scale utility grid-expansion plans have been denied by state regulators due to concerns over excessive costs.

Similar dynamics have slowed efforts within the independent system operators and regional transmission organizations that manage the grids that provide electricity to roughly two-thirds of the country’s population. Since a series of large-scale buildouts in the early 2010s, the scale of U.S. grid projects has declined significantly, with the average miles of newly built high-voltage transmission lines falling by more than half from the first half to the second half of that decade.

Several of these grid operators have approved multibillion-dollar grid buildout plans in the past two years. But those plans still tend to project lower levels of load growth than the data in Grid Strategies’ study indicates is on its way, Gramlich said. “It may be that everybody’s base case needs to be ratcheted up.”

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which regulates interstate transmission policy, is in the midst of crafting proposed transmission rules that are expected to require grid operators and utilities to examine a broader set of future grid needs, including increasing demand from electrification of transport and buildings, when making their long-term grid plans.

“There should be a lot of work coming up for every region following the FERC rule,” which is expected some time in the first half of 2024, Gramlich said. “That rule will require a lot of planning — and the devil’s in the details in every region.”

Building new power plants instead of transmission lines could help serve these growing loads. But it’s far more efficient to expand the grid to carry power from where it’s most cheaply generated to where it’s most acutely needed.

A host of new transmission grid projects have been approved over the past few years. But they’re still not enough to connect the massive amounts of new renewable power needed to reach the Biden administration’s goals of a zero-carbon grid by 2035. Studies from the U.S. Department of Energy, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Princeton University have found the country must double or triple current transmission capacity to reach that goal.

Nor are the new power lines being planned sufficient to eliminate rising grid-congestion costs that are adding billions of dollars to U.S. consumers’ electricity costs, or to enable different regions of the country to share power in order to mitigate the risk of blackouts during extreme winter storms or summer heat waves. This new report also adds the risk of stalling economic growth to this list of threats.

Transmission projects can take more than a decade to move from planning to construction, and they can be blocked by permitting and legal challenges at multiple points. Regional grid-expansion proposals can be scuttled due to conflicts between the utilities and states they connect over how to fairly allocate and distribute the costs of building them.

Federal action on this front has been limited as well. To date, Congress has failed to act on proposed legislation to offer tax incentives to transmission projects, to require minimum amounts of transmission between regions or to give FERC more authority to override state-by-state objections to new projects. But members of both parties in Congress “should care enough about infrastructure to support economic growth in this country,” Gramlich said.