When there’s only so much real estate available in urban centers for parks, how’s a developer to bring in more green with biophilic design?

By Kim Pexton

View the original article here.

Experts in the emerging field of biophilic design are finding that that people need regular contact with nature to be happy and whole. For those who live and work in cities, the concrete, glass towers, smog, and noise can drastically and negatively affect wellbeing. Urban areas are projected to house 60 percent of people globally by 2030, and one in three people will live in cities with at least a half million inhabitants.

So here’s the question and our opportunity: When there’s only so much real estate available in urban centers for parks, how’s a developer to bring in more green with biophilic design?

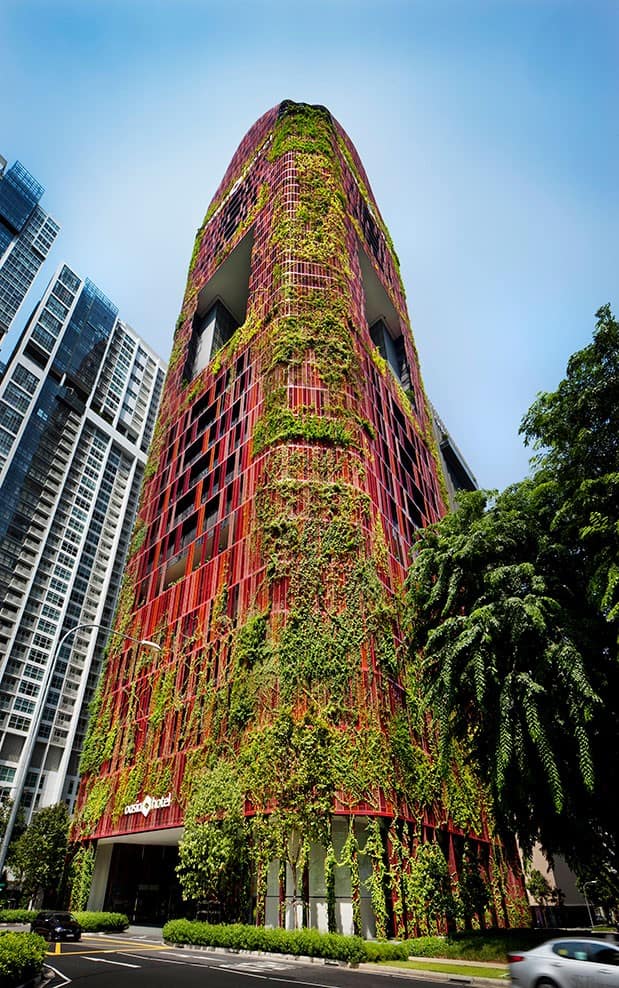

BUILD UP. MARRY BUILDINGS AND NATURE WITH VERTICAL GARDENS

Building designers are responding to the biophilic design call to action by creating vertical gardens. Also called living walls or green walls, vertical gardens are self-contained gardens installed on the sides of buildings to provide expanses of greenery in urban areas. Vertical gardens can be attached to virtually any vertical structure, and they can be used as free-standing space dividers, providing beauty, sound-proofing, and security. Plants can also be used to reduce noise along roads and highways. Living green walls block high-frequency sounds while the supporting structure can help diminish low frequency noise.

HERE ARE A FEW OF OUR FAVORITE EXAMPLES:

VERTICAL GARDENS ARE GOOD FOR THE COMMUNITY’S HEALTH

Prospective tenants – be they multifamily or commercial – love vertical gardens, which makes them a win/win for developers and building users.

Vertical gardens provide refreshing visual breaks from concentrations of concrete and steel, and their benefits go far deeper. Vertical gardens have a profound impact on air quality, especially in mitigating humidity and controlling dust indoors and outdoors. Green walls absorb noise pollution and create micro-climates that build heat efficiency. They have the added benefit of creating urban ecosystems that attract insects and birds, positively affecting biodiversity. In some cases, vertical gardens contribute to a larger ecosystem. In fact, vertical gardens take on more of a regenerative design philosophy from a C02 design standpoint. Plants are natural filters – taking carbon dioxide from the air and replacing it with much needed oxygen. They also help to filter pollutants from the air, literally helping urban dwellers breathe easier.

According to Hanging Gardens, a New Zealand vertical garden designer, the Auckland Council estimated the social cost from air pollution in the city to be $1.07 billion. Further, studies show that in city streets bounded by buildings, careful placement of plants reduced concentrations of nitrogen dioxide by up to 40 percent and of microscopic particulate matter by up to 60 percent. These statistics can be powerfully persuasive during design review meetings and entitlements processes.

Then there are the psychological benefits. The cumulative body of evidence from more than a decade of research on the people-nature relationship proves that contact with vegetation is highly beneficial to human health and well being. Whether contact with vegetation is active (gardening) or passive (viewing vegetation through a window), results show a consistent pattern of positive effects including:

- Psychological and physiological stress reduction

- More positive moods

- Increased ability to re-focus attention

- Mental restoration and reduced mental fatigue

- Improved performance on cognitive tasks

- Reduced pain perceptions and faster recovery in healthcare settings

Vertical gardens bring operational benefits too. One of the biggest benefits of vertical gardens is their ability to manage water. Vertical gardens make the need for watering very efficient, as the process is managed using a drip irrigation or hydroponic system. Waste water is collected at the bottom of the garden and either drained away or reused.

While vertical gardens have undeniable benefits for developers and building users, they can be challenging to design and maintain if they are not planned and installed properly. It’s critical to bring together the right system, plants, design, and maintenance strategy so that the green wall can serve the project in the long-term. The planning and investment will be worth it.