We’re completely rethinking our approach to packaging to use less, better or no plastic.

View the original article here

The challenge

Plastic is a very useful material for getting our products to consumers safely and efficiently. It’s often the lowest carbon footprint option compared to other materials. However, plastic is ending up in our environment. This has to stop.

Global research has shown that without action, twice as much virgin plastic will be created and three times more plastic could flow into our oceans by 2040. The plastic we produce is our responsibility. It’s clear we must reduce the amount of virgin plastic we use and completely rethink our approach to packaging. We must also keep plastic in use for as long as possible in a circular loop system. That means we need much better systems to collect, process and repeatedly reuse it.

We’re working hard to make progress in our business, but we can’t turn the tide on plastic pollution alone. To achieve a circular economy for plastics, we need strong commitments to be supported by systems-level change. Policy and regulation can play a critical role in tackling plastic waste, improving waste management infrastructure, and creating the right enabling environment for a circular economy. That’s why we’re calling for a global UN treaty with legally binding targets.

We also support policies like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), where companies pay for the collection of packaging – a key ask of the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty. We believe that well-designed EPR schemes are a game-changer in tackling plastic pollution. They ensure money is invested back into waste management and packaging innovation, and hold businesses to account for the packaging choices they make. In 2021, we signed a public statement with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation calling for the implementation of well-designed EPR policies, recognising that, without EPR, packaging collection and recycling is unlikely to be meaningfully scaled. Read more about how we’re using our voice to fix the broken plastic system through our advocacy and partnerships.

Our mantra and framework: Less plastic. Better plastic. No plastic.

We’re making progress towards our ambitious plastics goals, guided by the following framework:

- Less plastic: cutting down how much plastic we use in the first place through lighter designs, reuse and refill formats, and concentrated products which use less packaging.

- Better plastic: making sure the plastic we use is designed to be recycled and that our products use recycled plastic.

- No plastic: using refill stations and formats to cut out new plastic completely and switching to alternative packaging materials such as paper, glass or aluminium.

Our actions on all three are key to delivering our virgin plastic reduction goal. Due to our step up on recycled plastic, we’ve reduced our virgin plastic footprint since 2019 by 18%.

Our plastic packaging footprint

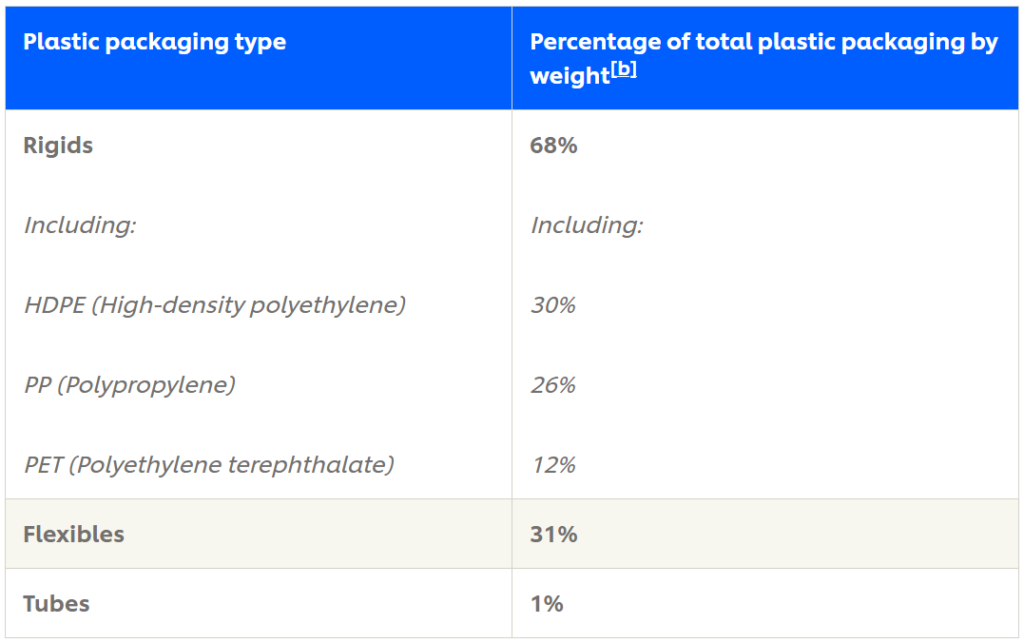

We use a variety of different plastic packaging types for our products.

Our total plastic packaging footprint – including virgin and recycled plastic – is made up of 68% rigid packaging materials, with bottles, such as those used for fabric cleaning liquid, shampoo and body wash, being the biggest contributor. Flexible packaging makes up 31% of our footprint, with sealed flexible packs and pouches, such as laundry detergent bags, contributing the most. The remaining 1% is made up of tubes, for example, those used for toothpaste

Less plastic

Sometimes a complete rethink of how we design and package products is the best way to reduce plastic. Reducing the amount of material in a product by just a few grams can make a huge difference across an entire product range. Over the last decade we’ve already cut the weight of our packaging by a fifth through better and lighter designs.

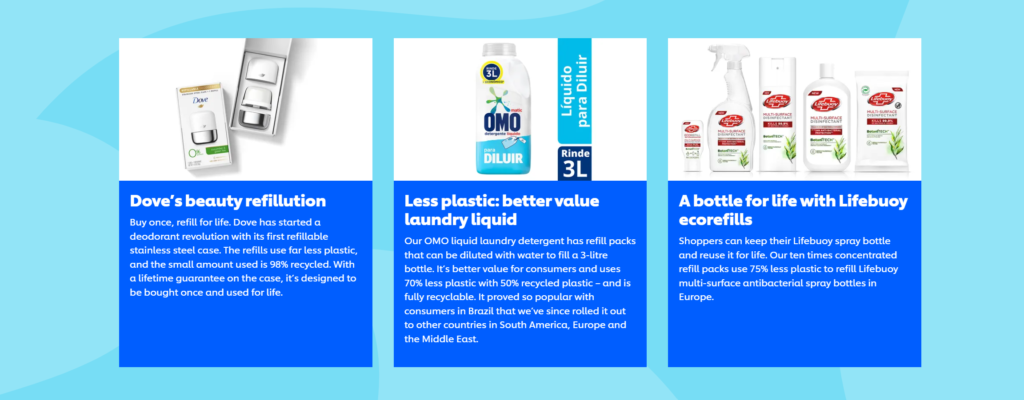

We’re encouraging consumers to think of bottles of our cleaning and laundry products as a ‘bottle for life’ – just like a ‘bag for life’ they might use for shopping. For instance, our OMO laundry customers can use their 3-litre bottles for life.

Ultra concentrated products help us give consumers the same products but with much less plastic and smaller packaging. Comfort’s ultra concentrated laundry formulas offer a smaller dosage than any other product on the market. Our Love Beauty and Planet concentred shampoos and conditioners provide the same number of uses with half the plastic.

Our Beauty & Personal Care brands are challenging our throwaway culture too. Dove has started a beauty ‘refillution’ with its first-ever durable, stainless steel refillable deodorant case which is designed to be used for life.

Better plastic

Whenever we use plastic, we make sure we’re choosing better options – that means recycled and recyclable plastics. Currently, 53% of our packaging is recyclable, reusable or compostable[c]. This is our actual recyclability rate, which is significantly less than the 72% of our packaging portfolio that is technically recyclable with existing technology. This gap is an industry-wide challenge and is primarily driven by a lack of collection and recycling infrastructure. We’re working with local governments and partners to close this gap, while we continue to deploy new materials and technologies.

We’re keeping plastics in the system, and out of the environment, by buying recycled plastic – sometimes called post-consumer recycled plastic (PCR). We’re ramping up how much recycled plastic we use. We’ve increased our use of recycled plastic to 22% of our total plastic footprint. This puts us on track to meet our commitment of at least 25% recycled plastic by 2025.

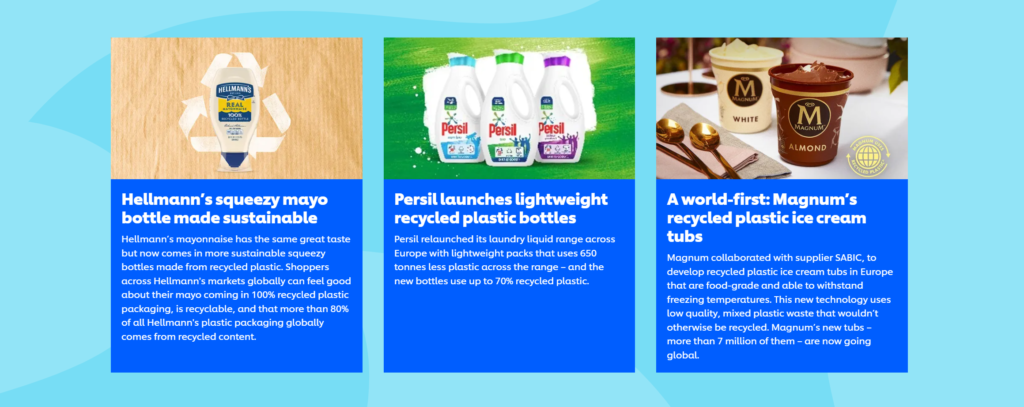

For instance, in 2021 Hellmann’s launched 100% recycled packaging in two-thirds of its markets, Knorr launched 100% recycled plastic bouillon tubs and lids in Europe, and Swedish Glace’s plant-based ice cream comes in recycled plastic tubs. Our Dove beauty brand uses 100% recycled plastic bottles in Europe and North America (where technically feasible) and 98% of its new refillable deodorant packaging in the US is made from recycled plastic. Our Love Beauty and Planet hair and skin care brand, is also working to incorporate recycled plastic in bottle caps and pumps.

There are plenty of technical challenges that we’re tackling in our better plastic journey. We’re developing new solutions, including chemical recycling for plastics which are hardest to recycle such as multi-layered and flexible packaging. We’re also aware that not all packaging that’s technically recyclable will actually be recycled. It’s technically possible to recycle around 72% of our product portfolio. However, what is actually recycled is lower because of the lack of infrastructure in communities.

Recycled plastic packaging also has to meet the same technical and safety standards as virgin plastic – standards which are higher for food packaging. Our Magnum ice cream brand worked with a supplier to overcome this challenge and launch recycled plastic ice cream tubs (see case study below).

In our Home Care division, our dilutable laundry detergents in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay are made with recycled plastic and cost less than undiluted detergents.

Collecting and processing plastic

We can’t reach our ‘better plastic’ goals unless there’s enough high-quality recycled plastic available. There’s no shortage of plastic in the system – but there are some big challenges. Turning plastic waste and pollution into usable material relies on local collection and sorting facilities. There also needs to be technical innovation and new solutions to make collecting and reprocessing materials commercially viable.

Our business in India was one of the first to help collect and process more plastic than it sold, and we have roadmaps for achieving this in other markets including Brazil, India, Indonesia, Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, UK and US.

However, we have more work to do to scale up our collection efforts. This includes direct investments, such as in the US where we’ve made a $15 million investment in the Closed Loop Partners’ Leadership Fund to help improve recycling. Partnerships in waste collection and processing, building capacity by buying recycled plastics, and supporting extended producer-responsibility schemes will also be critical to drive progress.

We’re developing technology-led solutions too. For instance in Indonesia, we’re supporting urban communities to develop systems to collect and sell waste. A digital platform called ‘Google My Business’ enables consumers to find their nearest waste banks via Google Maps. In China we’re using artificial intelligence to increase recycling rates (see case study below). And together with partners in the UK and US, we’re working to tackle the challenge of black plastic, which typically can’t be detected by waste sorting and recycling machines (see case study below).

We also need to consider the impact of the plastic system on people’s livelihoods, as plastic is frequently collected by waste collectors in the informal economy, often working under dirty and dangerous conditions and without earning adequate wages or receiving social benefits. These individuals and their communities are an integral part of the plastics solution, because without them we will not be able to scale up our collection efforts to meet our goals for a waste-free world.

This issue is a priority for Unilever, and we’ve been busy developing a global framework on how we approach and include human rights in our plastic value chain, especially for informal waste collectors who are involved in collection and processing in a number of developing markets. We’ve also been working with our peers and expert NGOs to build a common approach across industry – most notably through the Fair Circularity Initiative, which we co-founded and launched in November 2022 alongside Coca-Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo and the NGO Tearfund. Together, we have agreed to advance and adopt the initiative’s 10 Fair Circularity Principles and are now working towards implementing them.

In India, for example, we’re working with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to create a circular economy for plastic and support the social inclusion of thousands of workers within the informal waste sector – also known as waste pickers and Safai Saathis (which translates to ‘invisible environmentalists’) – in recognition of the critical role they play.

Finding new solutions for flexible packaging

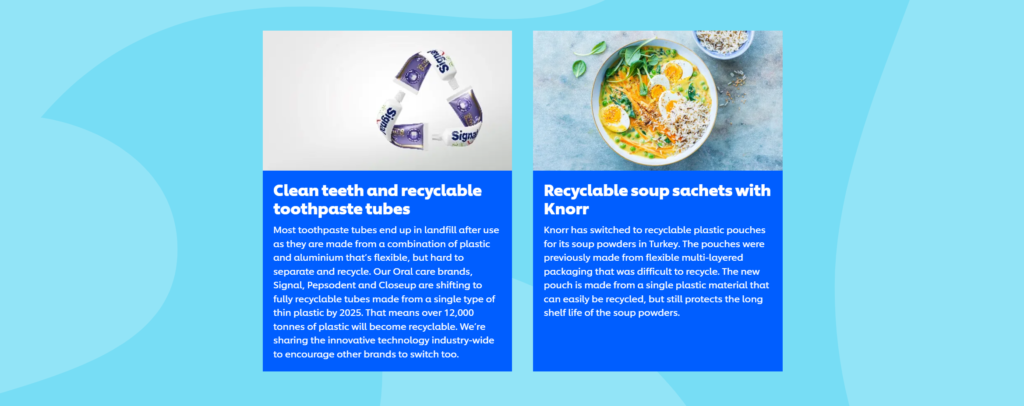

Plastic sachets allow low-income consumers to buy small amounts of products – often ones that provide hygiene or nutrition benefits like shampoo, food and toothpaste – that they would otherwise not be able to afford. However, flexible packaging, such as sachets and pouches, is particularly difficult to improve. In the long-term, we want to transition from using multi-layered sachets to mono-material sachets that are technically recyclable, and improve their collection and recyclability, particularly in our markets across Asia, where we sell more products in sachets. We’re learning there are no easy solutions. It’s a technical challenge, made more difficult by different local regulations on collection, sorting and recycling.

We’re developing new business models to reuse packaging and increase collection. For example, in the Philippines we have a sachet recovery programme to incentivise collection of post-consumer sachet waste in and around Manila. We’re also exploring how we can make sachets from single materials instead of multiple layers, making them easier to recycle. In Vietnam, we launched a trial for recyclable mono-material sachets of CLEAR shampoo. The recycled material is reused for items like refuse bags and containers, but with scale there’s potential to return it to our supply chain as recycled plastic. In Indonesia we’re testing solutions to eliminate the need for plastic by offering refill stations.

In Europe we’re members of CEFLEX, a consortium aiming to make flexible packaging in Europe circular by 2025. We contributed to an industry roadmap and guidelines exploring solutions.

We are committed to finding a solution for flexible packaging and we’re partnering with others to make progress.For instance in the UK we’ve partnered with other brands to launch the Flexible Plastic Fund to improve flexible plastic recycling rates. We’re working with Mars, Mondelēz, Nestlé, PepsiCo and UK retailers to incentivise the recycling of flexible packaging.

No plastic

No plastic means rethinking how we design products, developing whole new business models, and new shopping experiences for our consumers. It also means switching out plastic for alternative options such as metals, paper and glass.

The reuse-refill revolution

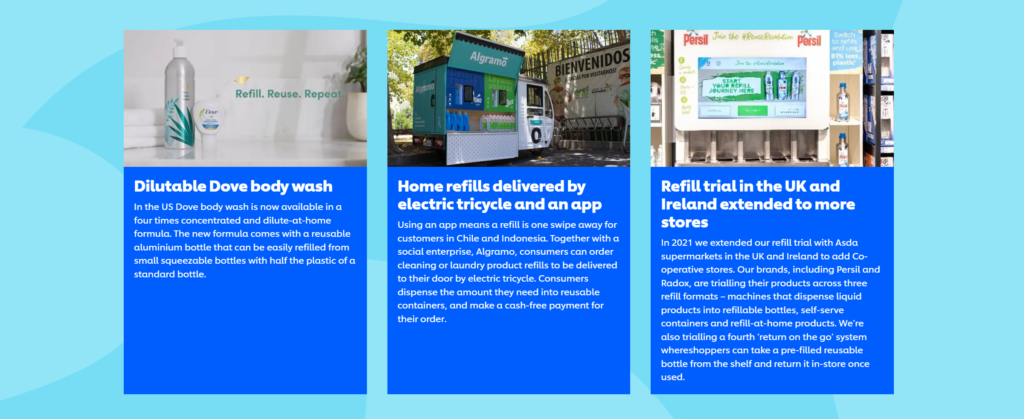

We want to help bring about a reuse-refill revolution. That’s why we’re working hard to find new ways for people to shop and use our products – for example, by buying one container and refilling it over and over again. Refills can be bought online or in a shop, or through in-store dispensing machines. A service could pick up empty containers, replenish them and deliver them back. Alternatively, people could return packaging at a store or drop-off point, as part of a deposit-return scheme (DRS).

We’ve been trialling a variety of reuse-refill models across our broad portfolio since 2018. We’ve conducted around 50 pilots across the world – testing and scaling different approaches, with the goal of making refilling our products as convenient, affordable and desirable as possible for consumers. Read more about the lessons that we’ve learnt along the way.

As we move beyond our initial ‘test and learn’ approach, we are working with partners, sharing our learnings and focusing our efforts to support an industry-wide shift towards reusable and refillable packaging at scale, in addition to scaling our own successful models. Collaboration is essential if we are going to get reuse-refill models working economically at scale.

Plastic-free packaging and products

We’re finding ways to remove plastic entirely from some of our products and packaging.

Our brands are using a range of alternative materials. Plastic-free packaging innovations include bamboo toothbrushes from Signal, fully recyclable paper food sachets for Colman’s, recyclable glass soup bottles from Knorr and paper ice cream tubs from Carte D’Or, Ben & Jerry’s and Wall’s. Persil laundry capsules now come in plastic-free boxes that can be fully recycled as paper in France. Dove’s single-bar soaps now come plastic-free and Seventh Generation also has a zero-plastic range on eCommerce channels in the US, using packaging made from steel.

We’re taking plastic out of our products too. Simple’s biodegradable facial cleansing wipes are made from sustainably sourced wood pulp and plant fibre.