While the industry plans more convenient, reliable charging stations with amenities, the needed growth in infrastructure remains immense.

By: Tim Stevens

View the original article here

Even zealots of the electric vehicle will tell you that public charging can be a fraught affair. If all goes well, and it often doesn’t, your charging session will likely entail sitting in a dark corner of a parking lot for upwards of an hour. You might have to stand in the rain or snow to operate the charger because most stations lack awnings. You might have to go hungry because many lack access to food. And, perhaps worst of all, your session may be made extra uncomfortable by a typical lack of restrooms.

But hopefully that’s changing. This year, Electrify America opened an indoor flagship location in San Francisco. Situated at 928 Harrison Street, this bank of 20 high-speed chargers is unique not only for its location—occupying some very expensive real estate—but also for its amenities. While charging, you can grab a drink from a vending machine, host a meeting from one of the lounges, and, yes, even use the bathroom.

ELECTRIFY AMERICA

It’s a massive upgrade from what many EV early adopters have become accustomed to, but it’s just the beginning. With familiar roadside refuges such as Love’s Travel Stops and Buc-ee’s getting in on the game, the future is finally looking a bit brighter when it comes to electrification’s infrastructure.

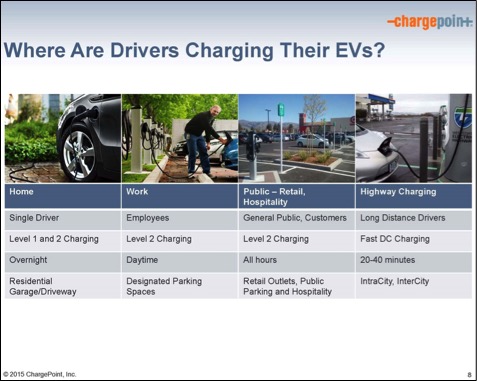

Just as with buying a new house, the three most important factors in EV charging are location, location, and location. After all, the fastest, most reliable charger in the world is worthless if it isn’t where you need it. The good news? If you have off-street parking, you can likely put a charger in the best possible spot: your home. More than 90 percent of EV owners charge where they live. While slower than the high-speed units at public stations, at-home chargers more than make up for it in convenience.

The latter can typically bring an empty car to full in under ten hours, which is plenty of time for most folks to replenish their EV’s battery pack between returning from work and heading out again the next day. That potentially means a full charge every morning, so public installations take a back seat for many who use an EV as their daily commuter. That’s why we need far fewer of them than we do gas stations. However, whether road-tripping or just going for an extended Sunday cruise, most EV owners will still need to replenish their batteries in the wild at some point. And while location is still crucial, other factors are gaining significance.

KENA BETANCUR/VIEW PRESS/GETTY IMAGES

Amaiya Khardenavis, an analyst of EV Charging Infrastructure at the energy-research firm Wood Mackenzie, says that there was a lot of “land grabbing” by the larger networks in the early days of EVs. That is, just throwing down chargers as close to major highways as possible with little regard for amenities. According to Khardenavis, today’s locations are more “customer-centric” than before. “The landscape in 2020 was dominated by only a few players in the market,” he says, “and these were all pure providers, like of course Tesla, but EVgo, Electrify America, ChargePoint, and that’s about it.”

Tesla gained an early advantage with its Supercharger network in 2012. Now, with more than 2,000 domestic locations, it’s the largest operator of fast chargers in the United States. But it wasn’t the first. ChargePoint is the nation’s largest network in general, launching back in 2007 and offering over 30,000 locations. Others weren’t far behind, including EVgo, which has about 3,000 chargers spread across 35 states.

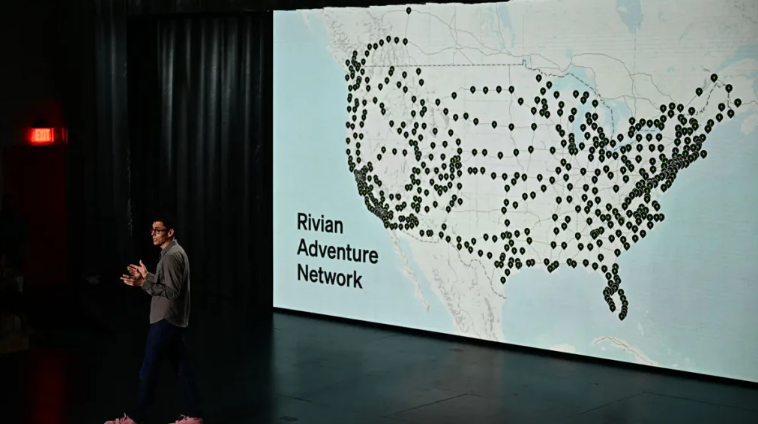

“We’re addressing a lot of our legacy equipment . . . some of our chargers are getting close to a decade old,” says Katie Wallace, EVgo’s director of communications. Yet some newer players are helping to raise the bar. One of those is EV manufacturer Rivian, which launched its Adventure Network just 18 months ago and has since deployed 433 fast chargers across 71 locations. “We’re opening sites each week,” says Sara Eslinger, director of the program for Rivian.

JUSTIN SULLIVAN/GETTY IMAGES

While the name “Adventure Network” infers that these chargers are at off-road trailheads, and indeed Rivian offers some of those, Eslinger says the company is still focused on serving major transportation corridors, while ensuring availability of amenities like 24-hour food services and restrooms, even going so far as to bring in their own lighting if necessary. As increased EV adoption pulls new investment from some familiar names, features like these are becoming the next battleground.

According to Khardenavis, “More retail stores, retail chains, and travel centers [are] entering the space—Walmart, Pilot, and Flying J, as well as Love’s, everyone is trying to be involved in this space to some extent.” Though many of these partnerships are still developing (Mercedes-Benz just announced a deal with Buc-ee’s in November, for example), the net result should be a significantly improved charging experience.

presentation last month.

PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Why are all these players getting into the market now? The money is starting to flow. In the beginning, running an EV-charging business was brutally complicated and expensive, and served only a small segment of early adopters. Today, utilization rates for public chargers are surging, and so is revenue.

“In our last earnings call, we reported that EVgo’s network throughout was growing five times faster than EVs in operation,” Wallace says. She adds that people are getting more comfortable driving their EVs, relying on chargers further afield.

Anthony Lambkin, vice president of operations at Electrify America, sees the same trend: “Some of our sites, especially in parts of California, are routinely over 50 percent utilization.” Lambkin refers to this as “massive growth,” and that it has driven the company to redesign some of its chargers, which were not up to surviving that intensity of use. Higher utilization means more money, and more money means more profits. But, as volume increases, so does the opportunity for other revenue streams.

retail-store component.

ALEJANDRA VILLA LOARCA/NEWSDAY RM VIA GETTY IMAGES

“In today’s gas-station business model, over 60 percent of the revenue really comes from store purchases, not from fuel retail,” Khardenavis says. “The future of the EV-charging model will be some sort of co-located retail-store presence.” More chargers at nicer locations, though, means nothing if they’re constantly broken. “The bigger question is going to be how reliable are these chargers?” Khardenavis says. A 2022 study out of the University of California, Berkeley, found that roughly one out of four chargers evaluated in the Greater Bay Area was non-functional (Tesla stations were not included). More troublingly, when the researchers visited those sites a week later, nearly all of them were still not fixed.

Khardenavis says that such historically poor reliability is directly related to profitability: “I think with that kind of cash flow coming in . . . there is now an impetus to develop this model, which is more customer-centric than just earlier focusing on expanding to locations.”

JOHN TLUMACKI/THE BOSTON GLOBE VIA GETTY IMAGES

In the world of public charging, there’s Tesla’s Supercharger network, and then there’s everybody else. Tesla’s network not only earned a reputation for being the most readily available and reliable, but using a single plug across every new Tesla model meant owners only had to show up, plug in, and wait while the electrons flowed.

Various plug standards have come and gone for other manufacturers, but that too is changing. Virtually every major manufacturer has agreed to use what’s being called the North American Charging Standard. It’s essentially the same plug that Tesla uses.

Soon EVs from Ford, Rivian, and plenty of others will not only use the same plug, but will be able to easily charge at Tesla’s Supercharger stations across the nation. That’s the good news. The bad news is that all the non-Teslas on the road today use a combination of different plugs, most featuring the Combined Charging System, or CCS. While Tesla is updating some of its Supercharger installations to support CCS, it’s going to be a slow transition. “We’re going to be in a land of adapters for a while, because the soonest that any non-Tesla OEM is going to come out with the NACS port is probably the fall of 2025,” says Wallace.

Tesla’s Supercharger stations across the nation.

CELAL GUNES/ANADOLU AGENCY VIA GETTY IMAGES

Rivian has updated its vehicles to show the location of all Superchargers on its integrated navigation, routing drivers appropriately depending on whether they have an adapter. Yet Khardenavis is concerned that this transition could slow down EV adoption further, with some buyers deciding to wait for the port transition to be completed before investing in a new EV. He fears that EVs with the “now-obsolete” CCS port could sit on dealership lots for longer.

Increased utilization raises the potential for long lines at chargers, but the process of building new stations entails dodging numerous roadblocks. One of those is working with local municipalities, which often aren’t used to moving at the pace of a startup. Electrify America’s Lambkin says that processes are improving, but it’s still a challenge. “Permitting is going much better for us now than it was five years ago because there are far more cities and towns and municipalities that are used to seeing this type of equipment,” Lambkin says. “Back in the day, it was like alien technology.”

The federal government is helping as well. The 2021 National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program provides funding to help cover planning, construction, and even maintenance of chargers. “Folks are going to see a lot more stations coming online in the next year and a half,” says Wallace, who attributes this to the various Department of Transportation outposts at the state level becoming “more comfortable and more familiar with how to implement the NEVI program.”

JIM WATSON/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Another issue is grid capacity. Khardenavis notes that, for a larger installation, it can take upwards of a year just for the necessary upgrades to power the site. “Project delays are a very common theme in the fast-charging space especially,” he says. But the charging companies are finding ways around this, too. According to Lambkin, Electrify America routinely uses on-site batteries to offset energy usage during peak times and has a so-called “mega pack” in Baker, Calif. “That’s actually to allow us to build that site well in advance of when the utility, SCE in this case, had the capacity to be able to serve the number of dispensers and the amount of power that we needed.”

And finally, there’s construction. It takes time to design a given charger layout, run the conduit, lay out the chargers themselves, and wait for all that concrete to cure. Even that process is changing. “We just deployed our very first station using prefabrication in Texas,” says EVgo’s Wallace. “It’s just a more efficient way to deploy because everything is assembled off-site, in an assembly facility, and then dropped into a skid-frame. So this construction timeline is much shorter.”

GEORGE FREY/GETTY IMAGES

According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), current growth and demand for EVs will require 1.2 million U.S. public chargers by 2030. As to the current reality, Khardenavis notes that there are about 165,000 available today, and he’s skeptical about that 2030 target. “It’s almost ten-X growth, which is extremely challenging in today’s environment,” he says, adding that predicting the need for six years in the future is itself difficult given the unpredictability of consumer behavior. “I don’t see us reaching that number anytime in the next four- to five-year timeframe. But I think it’s a target that we need to have in mind before we deploy and make plans around making EV charging more ubiquitous.”

SHELBY TAUBER FOR THE WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY IMAGES

But merely adding more chargers isn’t enough. It’ll take a better all-around charging experience to meet the needs of a new generation of luxury EV owners, such as drivers of the Mercedes-Benz EQS and the Rolls-Royce Spectre, for example. Meeting those standards will take more installations like Electrify America’s indoor flagship. “We’re really competing with the traditional fueling industry, and that’s been around for 100 years,” says Lambkin. “If you think about where we are today and where we’ve come in just five years, think about the levels of improvement that we can expect to see over the next five years.”

While that dingy charger in the back of the shopping-mall parking lot is still the norm for now, there’s work underway to make it the outlier. The real issue remains whether public adoption of EVs and the requisite infrastructure expansion will both maintain enough juice.

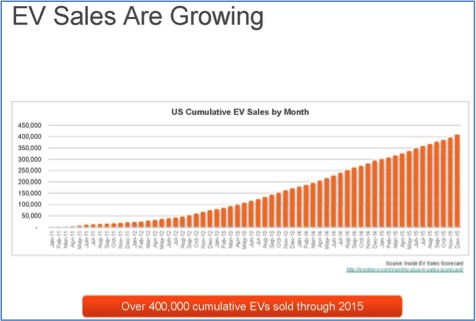

Five years after the first mass-market electric car hit the market, plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) have not met with the success expected, but they are pacing the rate of hybrid cars. Numerous challenges are being overcome in the evolution of the electric vehicle – not least of which is the automakers approach to the production and marketing of the cars, the range EVs travel on one charge and the availability of charging stations.

Five years after the first mass-market electric car hit the market, plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) have not met with the success expected, but they are pacing the rate of hybrid cars. Numerous challenges are being overcome in the evolution of the electric vehicle – not least of which is the automakers approach to the production and marketing of the cars, the range EVs travel on one charge and the availability of charging stations.