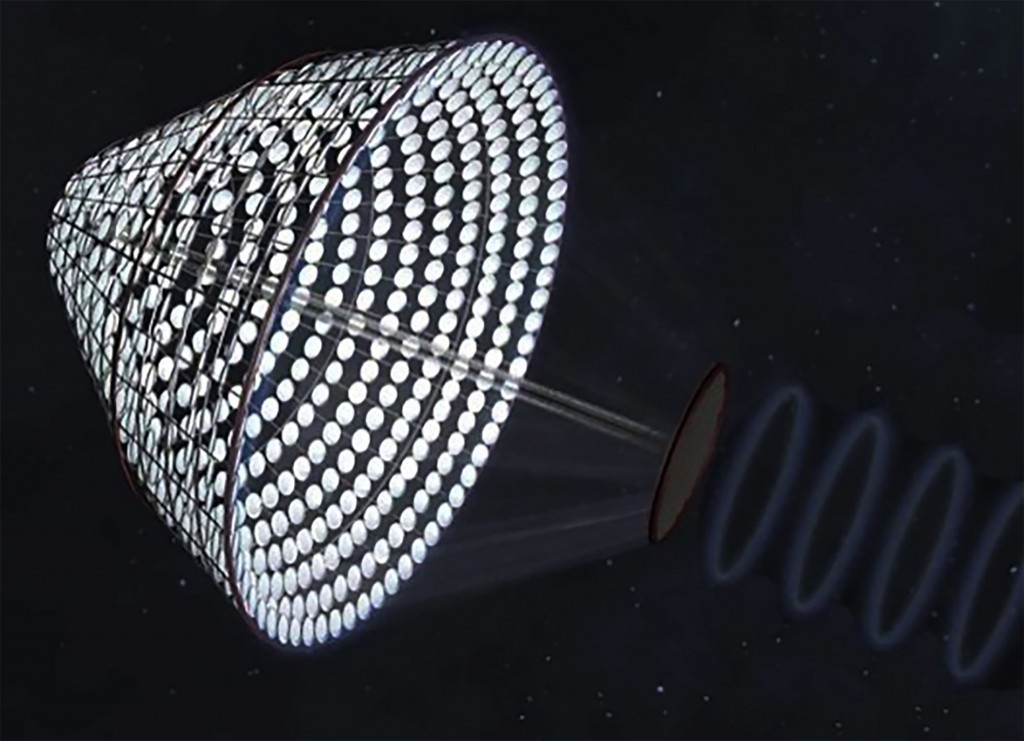

Space-based solar power is seen as a uniquely reliable source of renewable energy. NASA / Artemis Innovation Management Solutions LLC

China wants to put a solar power station in orbit by 2050 and is building a test facility to find the best way to send power to the ground.

By Denise Chow and Alyssa Newcomb

View the original article here.

As the green enery revolution accelerates, solar farms have become a familiar sight across the nation and around the world. But China is taking solar power to a whole new level. The nation has announced plans to put a solar power station in orbit by 2050, a feat that would make it the first nation to harness the sun’s energy in space and beam it to Earth.

Since the sun always shines in space, space-based solar power is seen as a uniquely reliable source of renewable energy.

“You don’t have to deal with the day and night cycle, and you don’t have to deal with clouds or seasons, so you end up having eight to nine times more power available to you,” said Ali Hajimiri, a professor of electrical engineering at the California Institute of Technology and director of the university’s Space Solar Power Project.

Of course, developing the hardware needed to capture and transmit the solar power, and launching the system into space, will be difficult and costly. But China is moving forward: The nation is building a test facility in the southwestern city of Chongqing to determine the best way to transmit solar power from orbit to the ground, the China Daily reported.

REVISITING AN OLD IDEA

The idea of using space-based solar power as a reliable source of renewable energy isn’t new. It emerged in the 1970s, but research stalled largely because the technological demands were

thought to be too complex. But with advances in wireless transmission and improvements in the design and efficiency of photovoltaic cells, that seems to be changing.

“We’re seeing a bit of a resurgence now, and it’s probably because the ability to make this happen is there, thanks to new technologies,” said John Mankins, a physicist who spearheaded NASA efforts in the field in the 1990s before the space agency abandoned the research.

Population growth may be another factor driving the renewed interest in space-based solar power, according to Mankins. With the world population expected to swell to 9 billion by 2050, experts say it could become a key way to meet global energy demands — particularly in Japan, northern Europe and other parts of the world that aren’t especially sunny.

“If you look at the next 50 years, the demand for energy is stupendous,” he said. “If you can harvest sunlight up where the sun is always shining and deliver it with essentially no interruptions to Earth — and you can do all that at an affordable price — you win.”

MAKING IT A REALITY

Details of China’s plans have not been made public, but Mankins says one way to harness solar power in space would be to launch tens of thousands of “solar satellites” that would link up to form an enormous cone-shaped structure that orbits about 22,000 miles above Earth.

The swarming satellites would be covered with the photovoltaic panels needed to convert sunlight into electricity, which would be converted into microwaves and beamed wirelessly to

ground-based receivers — giant wire nets measuring up to four miles across. These could be installed over lakes or across deserts or farmland.

Mankins estimates that such a solar facility could generate a steady flow of 2,000 gigawatts of power. The largest terrestrial solar farms generate only about 1.8 gigawatts.

If that sounds promising, experts caution that there are still plenty of hurdles that must be overcome — including finding a way to reduce the weight of the solar panels.

“State-of-the-art photovoltaics are now maybe 30 percent efficient,” said Terry Gdoutos, a Caltech scientist who works with Hajimiri on the space-based solar research “The biggest challenge is bringing the mass down without sacrificing efficiency.”

For its part, the Caltech team recently built a pair of ultralight photovoltaic tile prototypes and showed that they can collect and wirelessly transmit 10 gigahertz of power. Gdoutos said the prototypes successfully performed all the functions that real solar satellites would need to do in space, and that he and his colleagues are now exploring ways to further reduce the weight of the tiles.

THE ROAD AHEAD

China hasn’t revealed how much it’s spending to develop its solar power stations. Mankins said that even a small-scale test to demonstrate the various technologies would likely cost at least $150 million, adding that the swarming solar satellites he envisions would cost about $10 billion apiece.

Despite its exorbitant price tag, Mankins remains a staunch advocate of space-based solar power.

“Ground-based solar is a wonderful thing, and we’ll always have ground-based solar,” he said. “For a lot of locations, rooftop solar is fabulous, but a lot of the world is not like Arizona. Millions of people live where large, ground-based solar arrays are not economical.”

Mankins hailed recent developments in the field and said he is keen to follow China’s new initiative. “The interest from China has been really striking,” he said. “Fifteen years ago, they were completely nonexistent in this community. Now, they are taking a strong leadership position.”