by Paul L. Jones, CPA, LEED Green Associate

by Paul L. Jones, CPA, LEED Green Associate

Emerald Skyline Corporation

America’s water treatment and supply networks were built in the decade following World War II – 60 to 70 years ago. The results of those investments fueled a generation of widespread economic growth, prosperity and improvement in public health. However, the thousands of miles of distribution pipes beneath city streets, the lengthy water transport and treatment infrastructure are now cracked and brittle. The bill to repair and renew America’s long-neglected water systems are now coming due – and it will not be cheap.

Distribution pipes, which run for thousands of miles beneath a single city, have aged beyond their useful life and crack open daily. Some assessments estimate the national cost of repairing and replacing old pipes at more than US 1 Trillion over the next 20 years. In addition, new treatment technologies are need to meet the Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Water Act requirements, and municipal water companies must continue to pay on their debts.

Add to the needed infrastructure costs, the impact of droughts and sea level rise which are affecting the three most populous states in the country (California, Texas and Florida) and water managers are seeking ways to reduce consumption – with price increases as one way to encourage conservation. The EPA has identified at least 36 states that have experienced, or can anticipate, some type of local, regional or statewide water shortage which will have a significant impact on both consumers and commercial facilities.

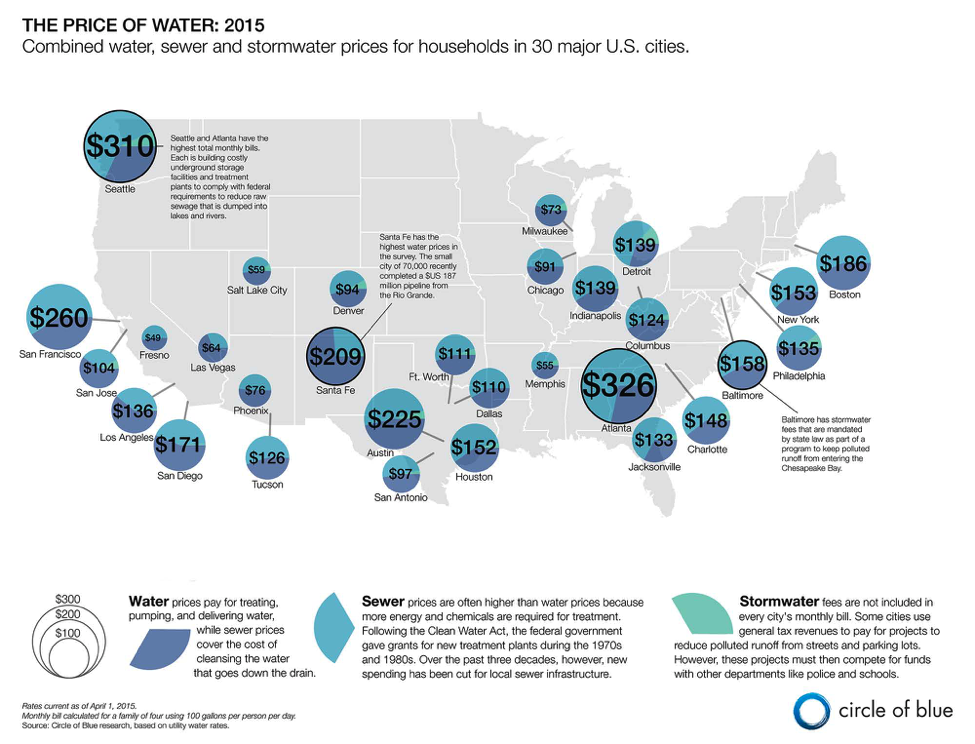

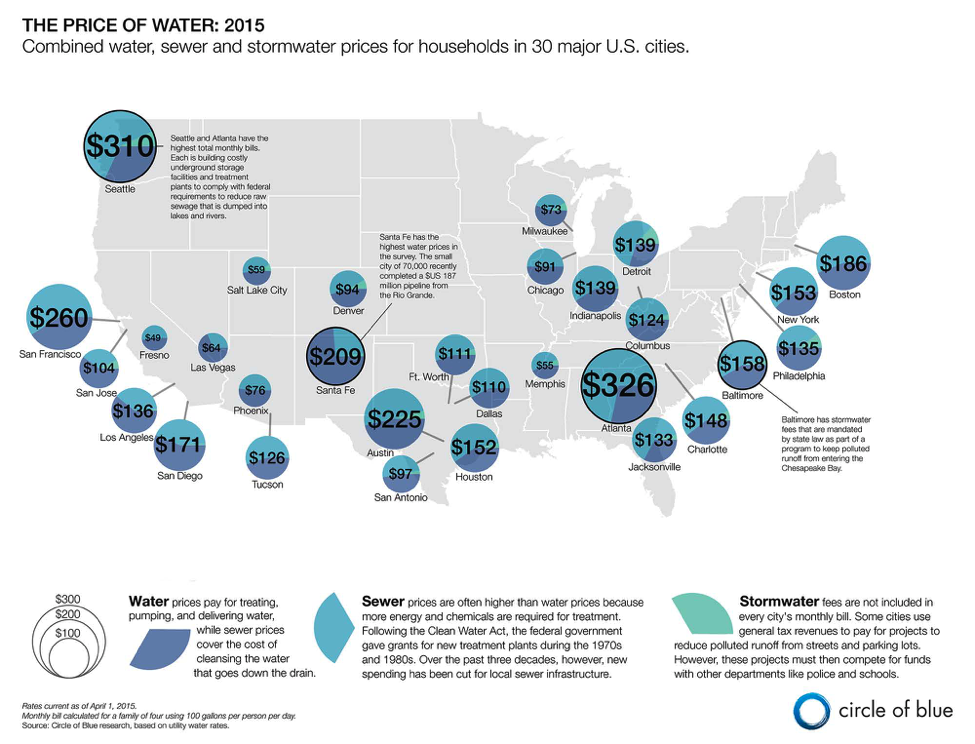

According to an annual pricing survey by Circle of Blue, the price of water rose six percent in 30 major US cities last year and it has risen 41% since 2010. Brett Walton, Circle of Blue, 4/22/2015

“In Chicago and neighboring communities that depend on the City for their water supply, a 25% rate increase took effect on 1/1/2012. The rate went up again in 2013 by 15%, and will increase again by 15% in 2014. That’s a 55% increase over a 3-year period. Even though American municipalities have traditionally underpriced water, a 55% increase in such a short amount of time is an indication that a serious problem exists – with no resolution in sight.” Klaus Reichardt, Environmental Leader, 10/14/2013

Further, more than 40 US cities are required to make massive investments in wastewater treatment capacity which are driving sewer rate increases as Federal grants that funded the current generation of sewage treatment facilities are no longer available so municipal utility companies must finance these projects on their own. In other words, they will be increasing sewer fees in order to keep our water clean.

“We expect water rates to continue to grow above inflation for some time. We don’t see an end in sight.” Andrew Ward, director of US Public Finance, Fitch Ratings.

It is clear that the cost of water and wastewater services are going to continue to increase at rates well above the consumer price index.

Commercial and institutional buildings use a large portion of municipally-supplied water in the United States. In fact, the EPA estimates that facilities such as schools, hotels, retail stores, office buildings and hospitals account for up to 17% of publicly-supplied and 18% of energy use. The three largest uses of water in office buildings are restrooms, heating and cooling, and landscaping.

Accordingly, implementing water-efficiency measures, while resulting in immediate savings will also serve to reduce the financial impact of future rate increases – a hedge against inflation, if you will. According to the EPA, which has established Water Sense at Work: Best Management Practices for Commercial and Institutional Facilities, “the benefits of implementing water-efficiency measures, in and around office buildings can include reducing operating expenses as well as meeting sustainability goals. In addition to water savings, facilities will see a decrease in energy costs because of the significant amount of energy associated with heating water.

Accordingly, implementing water-efficiency measures, while resulting in immediate savings will also serve to reduce the financial impact of future rate increases – a hedge against inflation, if you will. According to the EPA, which has established Water Sense at Work: Best Management Practices for Commercial and Institutional Facilities, “the benefits of implementing water-efficiency measures, in and around office buildings can include reducing operating expenses as well as meeting sustainability goals. In addition to water savings, facilities will see a decrease in energy costs because of the significant amount of energy associated with heating water.

NOTE: Water efficiency refers to long-term reduction in water consumption that is not in response to any current water shortages. Water-efficient systems enable a facility to meet users’ needs while using less water than conventional equivalents.

Water consumption in commercial and institutional buildings is dependent on many factors: The age of the building, the local climate, the use of the facility, the existence of a kitchen facility or restaurant amenity and the type and age of the HVAC system. However, in virtually all venues, the restrooms are the primary consumer of water. Accordingly, the best place for building owners and managers to start is the restroom.

Before introducing some water conservation strategies, the greatest impediment to achieving meaningful water savings in office buildings is the common disconnect between the accountant who pays the bills, the building owner, the tenants, the building manager or engineer and the various third-party contractors that maintain the facility and equipment. In multi-use or multi-tenanted properties, water saving potential is frequently great, but successful implementation of changes always requires a cooperative effort from all of the stakeholders.

Like an energy audit that identifies the main users of energy and benchmarks use, the best way to identify water conservation measures is to establish a water savings plan that benchmarks the ways water is consumed and prioritize them. Water conservation will vary in a commercial setting depending on the building type and use. While hospitals and office buildings require a large water volume for mechanical systems, hotels and restaurants require high usage in laundry and food service applications, respectively.

Determining the applications that have the greatest water consumption is critical to prioritize the overall goals and budget. One way to do this is by installing sub-meters in various facility locations (such as restrooms, cafeteria and food service areas, different floors or blocks of floors, etc.) and then monitoring water consumption in each area. This can provide insight into where water is being used and can also point out inconsistencies in water consumption—information that can sometimes result in significant savings.

For instance, a facility might find that one block of floors uses far less water than another block. Is this because there are fewer people on those floors? Or are there plumbing leaks or older fixtures in the block using more water? Tracking water use allows building engineers to move quickly to identify problem areas within a building’s water systems.

Once the systems and their water usage have been determined, a water savings plan can be developed. A water savings plan will inventory the systems in-place, identify water-efficient alternatives and estimates of the costs and benefits of each component of the plan. The benefits of water efficiency efforts can be measured by calculating the difference between what the building owners/managers previously spent on water and related operating costs and what they spend after water efficiency programs are implemented. The return on investment of new equipment, fixtures, and other water-related items can also be calculated over the lifetime of a water efficiency project, and includes such things as reduced maintenance, water, sewer, and related energy costs.

Typical Water Efficiency Plan Components

Below is a quick summary of how a typical commercial facility can use water more efficiently:

Toilets. Replace older toilets with fixtures that meet or exceed Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC) and International Plumbing Code (IPC) requirements: 1.6 gallons of water per flush. Some newer toilets, including high-efficiency and dual-flush models, use even less water than that. Facility System Solutions, in a 7/14/2014 article entitled “Mandated high-efficiency toilets pay off” reports that since being required by the Energy Policy Act of 1992 “low flow toilets have saved enough water to fulfill the needs of Los Angeles, Chicago and New York for two decades.” Further water reductions are achieved through dual-flush or high-efficiency EPA WaterSense-labeled toilets.

Faucets. Replace existing faucets or install restrictive aerators to reduce water use from approximately 2.2 gallons per minute to 0.5 gallons per minute.

Urinals. Again, replace older fixtures with newer models that use less water (one gallon of water per flush or less). However, facilities can achieve far greater savings by installing waterless urinal systems (unfortunately, many building codes do not allow these fixtures). Further, according to a study by the Rand Corporation, waterless urinals often provide a significant savings due to their lower annual maintenance costs, in addition to the benefits incurred from reduced water use.

Alternative water sources. Some facilities, and even some legal jurisdictions, have installed or are planning to install “greywater” distribution systems. Grey water is tap water soiled by use in washing machines, tubs, showers, and bathroom sinks that is not sanitary, but it’s also not toxic and generally disease-free. Grey water reclamation is the process that capitalizes on the water’s potential to be reused instead of simply piping it into a sewage system. While this water is considered non-potable (that is, not for human consumption), it can usually be used for toilets and traditional urinals, as well as for plant/landscape irrigation in some cases.

Another “alternative” water source is rainwater which can be harvested where capturing and storing rainwater is an easy and effective way to conserve water through a commercially viable payback period. Selecting a rainwater harvesting system is dependent on the collection area of the commercial site and the intensity of rainfall in the particular region of the country. Once the availability and demand are calculated, the system should be designed to meet the daily demand throughout the dry season.

Cooling tower water recovery is another “alternative” source of water. Cooling towers remove heat from a building’s air conditioning system by evaporating some of the condenser water. Since all cooling towers continually lose water through evaporation, drift, and blowdown, they can consume a significant percentage of a building’s total water usage. Towers that are in good condition, operated properly, and well maintained allow chillers to operate at peak efficiency. Some cooling towers can use recycled water like stormwater or grey water if the concentration ratio is maintained conservatively low. Similarly, blowdown water may be reused elsewhere on-site.

Leak Detection. In most cases, leaky restroom fixtures and pipes are only fixed when they become excessive or cause problems, such as water pooling on floors. Leak detection systems in critical or remote locations tied to a BAS to notify maintenance staff of water leaks ensure a quick response before building walls, ceilings, and equipment are permanently damaged. A formal leak detection program—in which building engineers regularly check all fixtures and major plumbing connections on a set schedule — can save literally thousands of gallons of water annually.

And, finally, educate the users. Water conservation is not only about innovation and good design practices, but also about building an understanding among water consumers to work together to achieve a greener and more energy-efficient environment. It is important to educate users about water scarcity issues and the impact of water conservation practices through signage and awareness campaigns at the point of use.

Conclusion

Usually overshadowed by high-efficiency HVAC systems or LED lighting retrofits in commercial building modernization and sustainability programs, water is increasingly becoming a scarce commodity and implementing a water conservation plan may just be the low hanging fruit of sustainable benefits. From the invention of a water-leak detection system to implementing sustainable retrofits, the Emerald Skyline team can provide you with the tools and guidance you need to save money by saving water.