The world cannot transition to a cleaner energy mix without storage and grid stability – and that’s where batteries come in. In the coming years, the energy storage market will expand rapidly, as regulations smooth the path and costs come down.

By Shelby Tucker

View the original article here

Key Points

- The global energy storage addressable market is slated to attract ~$1 trillion in new investments over the next decade.

- The US market could attract over $120 billion in investment and achieve growth rates of 32% CAGR thru 2030 and 15% CAGR thru 2050.

- Energy storage costs are estimated to decline 33% by 2030 from $450/kWh in 2020.

- Lithium-ion will continue to dominate the market, but there’s no one-size-fits-all – different applications utilize specific technologies better than others.

- The regulatory and policy path still looks slightly rocky, but there’s no question that storage is needed, as grids cannot efficiently use renewable energy without it.

Energy storage has been seen as the next big thing for some time now, but has been slow to live up to its promise. Cost reductions were always inevitable, because a renewable energy-powered grid can’t function without some storage capacity. But technological advances have been incremental and there’s no one solution for all applications. Instead, different technologies have their place as the application trades off between power storage duration and degradation, speed of discharge back onto the grid, and costs.

The new energy grid

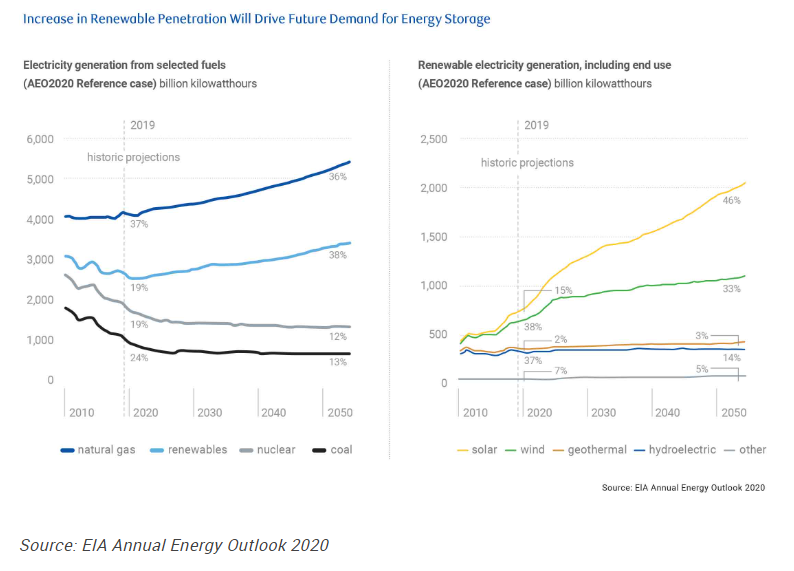

The energy produced by solar and wind is intermittent, which is altering the structure of power grids all over the world as these technologies begin to dominate generation. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) now expects renewables to supply as much as 38% of total electricity generation by 2050, up from 19% in 2020. This shift in generation mix brings a cleaner energy future but it also adds complexity to the energy grid. Higher renewable penetration makes energy supply less predictable. Not only does the grid need a way to supply power when the weather doesn’t behave, but when the sun shines and the wind blows, the energy grid must be able to handle the additional stress of lots of power coming online.

This requires active energy management and a grid that can react within seconds instead of minutes. It all comes at the same time as demand continues to grow, requiring more power, more efficiently, all while meeting tighter environmental standards.

How batteries power the new grid

Sophisticated battery energy storage systems (BESS) are the only solution to the future grid, but the form that they take is still in flux. BESS enables a wide range of applications, including load-shifting, frequency regulation and long-term storage, and its deployment tends to be decentralized and far less environmentally intrusive than traditional pumped-storage systems.

Battery technology has come a long way, and lithium-ion has emerged as the dominant chemistry, with an unparalleled profile. But there are still trade-offs, broadly in terms of high power versus high capacity configurations. This means a wide variety of BESS are in use, and in development, to serve various functions. BESS are deployed at various points of the electric grid depending on the application. For example, it may serve as bulk storage for power plants as a generation asset. As a transmission asset, it may function as a grid regulator to smooth out unexpected events and shift electric load.

Each battery application requires a specific set of specifications (i.e. capacity, power, duration, response time, etc.). This in turn determines the chemistry and economics of the BESS configuration.

Which battery?

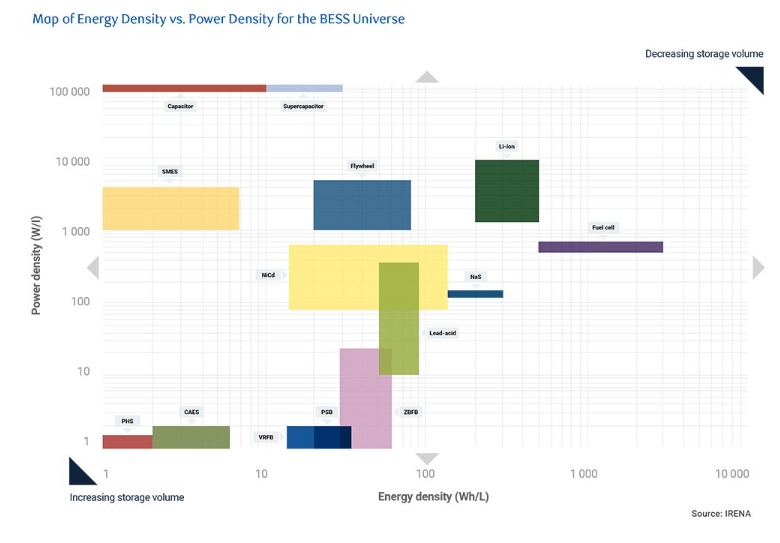

The electrochemical battery is by far the most prevalent form of battery for grid-scale BESS today. And within the electrochemical world, lithium ion (Li+) dominates all other chemistries due to significant advantages in battery attributes and rapidly declining costs. But there are other options. Within electrochemistry, sodium sulfur (NaS) thermal batteries feature energy attributes similar to those of Li+, potentially making it a close competitor for BESS in the future. Development of lithium-based technology hasn’t stopped either, with solid state batteriesand lithium-sulfur (LiS) batteries both showing promise, for stability and affordability, respectively.

Flow batteries are another potential electrochemical choice, while hydrogen fuel cell batteries, synthetic natural gas, kinetic flywheels and compressed air energy storage all have strengths for different applications on the grid. Fuel cells in particular could become a strong contender in the future for long-term storage, considering its strong advantage in energy density.

While Li+ does dominate the market, alternative battery technologies may still be able to corner niche markets. At one end of the duration spectrum, pumped hydro and compressed air systems will continue to be attractive for seasonal storage and long-term transmission and distribution investment deferral projects. At the opposite end of the duration spectrum, we may find flywheels popular for very short duration applications due to the significantly higher response times and efficiency relative to Li+.

Calculating the cost

The function and utility of a BESS requires careful calculation, which also has to be balanced with cost. And cost itself isn’t easy to count. Assessing the true cost of storage must account for the interdependencies of operating parameters for a specific application. The complexity also rises as the number of applications increases. Fortunately, the growing use of energy management software should improve optimal battery operating decisions and improve cost calculations over time. A common standard to compare cost of different battery assets is the levelized cost of storage (LCOS), which borrows from the widely accepted levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for traditional power generation assets and aims to discover the cost over the lifetime of the battery.

However the cost is calculated, what is certain is that it is falling. Lithium battery pack prices achieved momentous declines since 2010, dropping from ~$1,200/kWh to $137/kWh. Non-battery component costs are also falling, and we believe that overall costs will reach $179/kWh by 2030.

Policy and regulations

The final piece of the puzzle lies in government support for energy storage. Currently, energy storage policies vary widely across state lines. A handful of frontrunners such as California, Hawaii, Oregon and New York are shaping energy storage policies primarily through legislative mandates and executive directives. Other states such as Maryland take a more passive approach by relying more on financial incentives and market forces. States like Illinois struggle to find the right balance among renewables, nuclear and fossil generation, resulting in policy limbo. Exceptions like Arizona are blessed with extraordinary amounts of sunshine and solar development so that the state requires little top-down guidance to incentivize energy storage development.

But despite the diversity on the state level, the country as a whole appears to be moving in the direction of higher amounts of energy storage. At the time of writing, 38 states had adopted either statewide renewable portfolio standards or clean energy standards. As of 2020, energy storage qualifies for solar federal investment tax credits (ITC), which allows a deduction of up to 26% of the cost of a solar energy system with no cap on the value as long as the battery is charged by renewable energy. ITCs used for energy storage assets face the same phase down limitations as solar assets.

Congress is currently evaluating a standalone ITC incentive as part of President Biden’s Build Back Better Act. We believe passage of a standalone incentive could further accelerate the demand for energy storage assets.

Nascent technologies may change the mix of storage solutions, but the industry will continue to grow rapidly in the coming years. Falling costs and federal and state support will grease the wheels, but the reality is that storage is a necessity for a grid that’s powered by renewable energies. That imperative will keep investment dollars pouring into this space.