December 11, 2013

Part 1: Five Years of Advancing Deep Retrofits

View the original post here

Since 2009, RMI’s work to advance deep energy retrofits has focused on a multi-pronged approach to scaling: 1) collaborate with project teammates, owners, and other fast movers who learn from and copypioneering deep retrofit projects, 2) engage entire portfolios and campuses of buildings to impact more than scattered singular building retrofits, and 3) develop new, better, and more comprehensive ways of assessing risk and value associated with deep green buildings, to drive greater investment by financial decision makers.

In today’s part one of a three-part series, we take a look at RMI’s work advancing deep retrofits. (Read parts two and three.)

Five years ago RMI embarked on a body of work to advance what we call deep retrofits, energy-efficiency retrofits that save 50 percent or more of a building’s energy consumption. Half a decade later, it’s time to reflect on how far we’ve come with our Retrofit Initiative … and how far we still have to go.

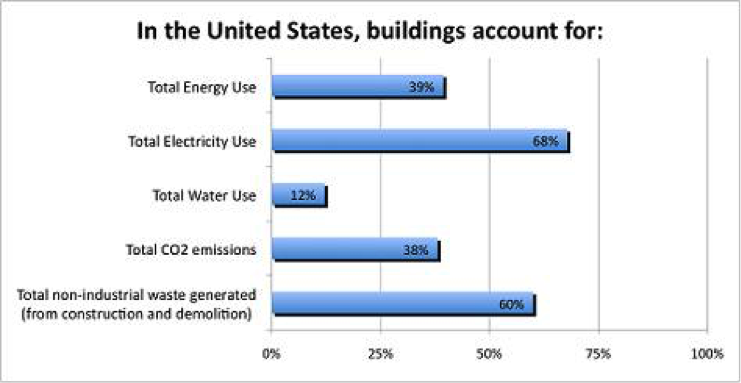

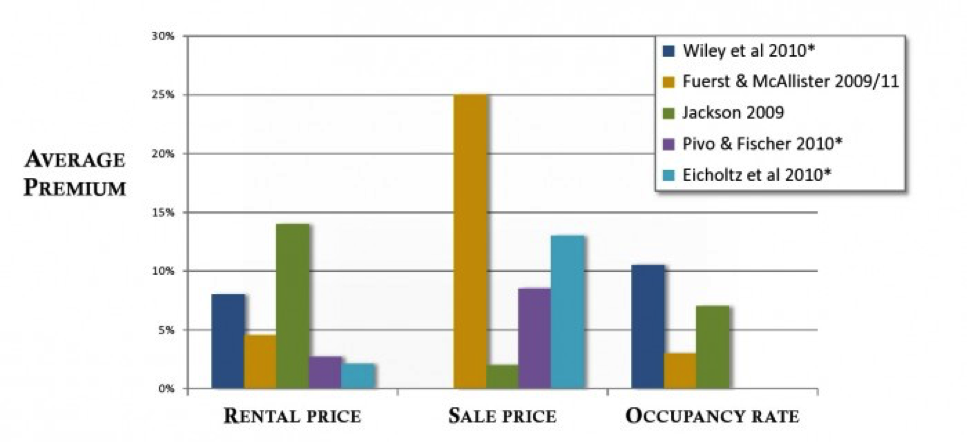

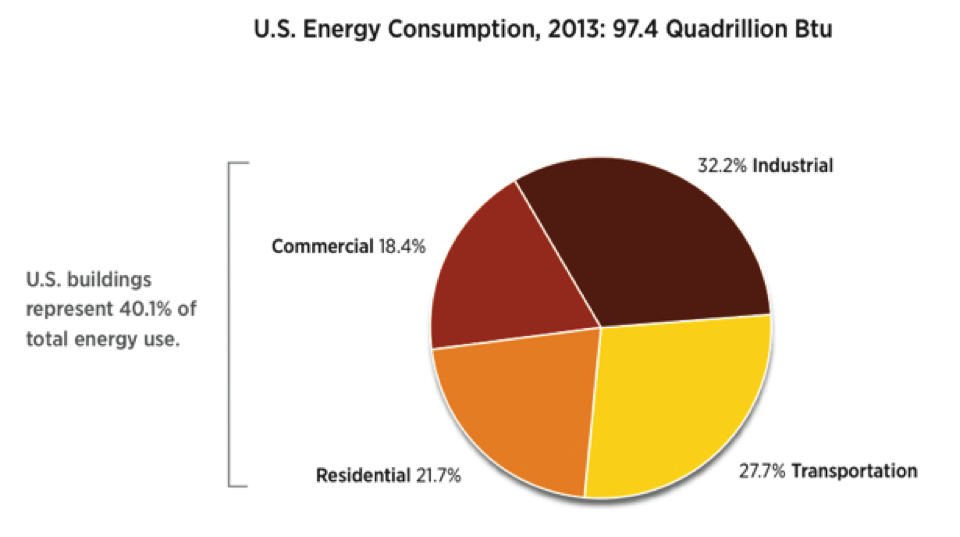

First, though why a focus on such profound energy efficiency? For starters, we care a lot about eliminating wasted energy, and that’s what most building energy consumption is: waste. But this is about more than simple waste. Done well and timed right, eliminating that waste makes good money. Further—and maybe most importantly—a highly efficient building (whether new or upgraded) is more comfortable, healthier, enables higher productivity, and generally entices people to stay in it longer. Finally, it’s increasingly important for employers and institutions alike to be able to say, and show, that they occupy high-quality, green buildings that perform both financially and environmentally. Real estate markets, especially in certain regions, are waking up to a new and powerful competitive dimension that RMI is helping create!

Our Buildings Practice is working on all these dimensions, mostly in commercial buildings. Five important examples form the core of our retrofit work on individual buildings; work aimed at “Making Old Buildings Better Than New (Ones).” They are:

- Empire State Building (New York City)

- City-County Building (Indianapolis)

- IMF Headquarters 1 (Washington, D.C.)

- Byron Rogers Federal Building (Denver)

- The Clark Museum (Williamston, MA)

And while our initial engagement on such projects was funded by the projects themselves, everything that followed, including educating the buildings industry and scaling solutions, comes form donor-funded dollars. Buildings work is often slow to show results. The work only just starts with the conceptual and system-level interventions that RMI has pioneered. Several years often pass before the physical work is done and the “verdict” is in with real measurements showing results. Fortunately for RMI, some of our focus has also been on helping advance the role of sophisticated modeling tools that give a very good sense of what to expect. For some of our fab five examples, the full story is still not in, but the answer is pretty clear. And the change we expect in the world is beginning to happen because of these results.

The Empire State Building

As one of the most famous buildings in the world, the Empire State Building (ESB) is well known, and so is its deep retrofit, one of the first ever in the world on a commercial building. While not yet completed in all tenant space, it is already clear that the retrofit will save more energy than the 41 percent modeled—and command far higher rents.

But the project was notable as well for what followed—RMI’s subsequent work crafting a replicable methodology for deep energy retrofits, sharing lessons learned, building free tools for service providers, and meeting with government officials about the economic benefit of promoting deep energy retrofits. This follow up profoundly moved the market. Over the past two years, ESB design team members alone have begun the process of replicating their own versions of the deep retrofit model in close to 100 large buildings across the country, many in New York. Inside sources say the Empire State Building energy retrofit was a key factor in launching New York City’s groundbreaking Local Law 84: Commercial Building Energy Benchmarking. New York’s benchmarking efforts have spurred eight more municipal and state building energy disclosure policies in major U.S. cities, with more emerging. And RMI helped shape other city and New York state programs aimed at energy savings in buildings.

The City-County Building

Our next project after ESB was a famous—but infamously inefficient—government office building in Indianapolis. Many had tried to fix it. But both money and ideas were limited, and it was still a potential gold mine of energy waste when RMI was invited to help. That was in 2009. One year later, Indianapolis mayor Greg Ballard announced energy-efficiency upgrades for the building expected to reduce energy consumption 35 percent annually. Design-build firm Performance Services executed the retrofit under a performance contract that guaranteed $750,000 in energy savings per year for 15 years, completing the $8 million project at no cost to taxpayers. By 2012, the City-County Building had reduced its annual energy use by 46 percent and earned prestigious ENERGY STAR certification.

The Byron Rogers Federal Building

The Byron Rogers Federal Office Building followed on the heels of our City-County Building work. RMI teamed up with a major contractor, Mortenson, in 2010 and presented an aggressive plan to aim for net zero. This mid-century modern office building renovation—largely completed, but not yet fully re-occupied—is a powerful case study for dramatically improving performance of existing buildings through integrative design, regardless of barriers such as misaligned government mandates, historic designation, multiple tenants, hazardous materials, and poor orientation. This project work also formed the foundation of donor-funded focused studies and educational material on managing plug loads.

Building upon the Byron Rogers project, RMI worked further with the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) to better understand tenant issues. Working on another important accelerator—the service industry that executes the work—RMI teamed again with the GSA to prove that energy service companies (ESCOs) can be primary drivers and implementers for achieving deeper energy savings in buildings. Funded partly by donors, this effort intervened with sixteen of the largest ESCOs in the U.S. with a goal to introduce them to strategies for deep energy retrofits and to identify and overcome barriers to achieving the deepest efficiencies. Over the course of our partnership with GSA, average projected energy savings from the deep program’s ESCO engagements at GSA has already more than doubled to 39 percent from 18 percent. This marks a significant positive change in the “MUSH” institutional and government market that seldom achieved more than shallow savings and has in recent years been using ESCOs largely for lighting and equipment finance only—a case of leaving barrels of money on the table!

IMF Headquarters 1

At the same time as Byron Rogers, RMI had an opportunity to reshape how things are done in the nation’s capital, a sea of opportunity in the form of large, inefficient office buildings crowding the streets around the government buildings on the Mall. The client was the International Monetary Fund. Once again, RMI played a different role, not as a bidder for a project, but as part of a team to shape the brief for those bidders—to tell them what to do, in other words. After extensive option and life-cycle cost analysis the pre-bid team came up with a doozie: a winning project would need to cut energy use in half and meet other explicit financial and performance targets. Here is how the proud client talks about it: “The improvement under way will provide a more modern and energy-efficient setting. Energy bills will fall by nearly half—saving between $2 million and $2.5 million per year…”

The project is under construction now, to be completed in 2016. Importantly, the execution team, led by architect Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and engineer WSP Flack and Kurtz, will drive the insights and processes into the Washington real estate world and beyond.

The Clark Museum

One final test project was a real challenge: the Clark Museum on the campus of Williams College in Massachusetts. The opposite of the IMF project, where RMI helped shape what bidders would be asked to do, at Clark RMI was brought in after a design for a significant addition and retrofit was already almost complete. Way too late, we thought. But we wanted to test what was possible in this “worst case” situation where the key was a motivated owner (supported by a significant donor).

The problem in a building such as a museum—as in a laboratory as well—is achieving energy savings while maintaining a strictly controlled internal environment that protects art and artifacts in a curatorial environment. RMI identified and recommended opportunities to double HVAC energy savings compared to the design team’s energy model. Needless to say, the Clark (and RMI) donor backing the work was very happy … and recently sent a note saying so. The results are in, and the energy savings are rolling in as expected.

Scaling Our Impact

These exemplary projects are commendable, but the real goal is to spread their lessons and ideas far and wide. That’s why we created the RetroFit Depot as an extensive and compelling Web-based resource for building owners and professionals considering energy retrofits, including our acclaimed Deep RetroFit Guidelines. One consulting firm in Chicago says they used our guidelines as a foundation for twenty deep retrofit roadmaps within the Retrofit Chicago – Commercial Buildings Initiative. Our Buildings Practice staff members have presented over 100 educational sessions on how to plan for and conduct deep energy retrofits to a total combined audience in the tens of thousands in the past four years.

RMI also worked closely with the American Institute of Architects to develop Deep Energy Retrofits: An Emerging Opportunity, a guide for architects. The guide was launched during AIA’s annual conference in June in conjunction with a well-attended all-day seminar on deep energy retrofits. This industry intervention was donor-funded. RMI also teamed with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory to help produce a set of retrofit guides for different buildings categories (office, retail, healthcare, etc). Finally, RMI has shaped an educational agenda, one where we play specific roles to help all others understand the learning available, and the major holes still left to fill. Based on this agenda we have conducted half a dozen deep training sessions, focusing largely on a specific leverage point: engineering firms and ESCOs.

We’ve also testified to the U.S. House Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight on the impact and importance of fossil-fuel reduction targets and green building rating systems, and written almost 100 blog posts and web articles on energy-efficient buildings and campuses. Deep retrofits are one area of innovation and promise in driving greater building efficiency in order to enable a fantastic, sometimes better-than-new building, and even more importantly, foster a vibrant clean energy economy. We cannot lay the path nor spread that message without donor funding. If you believe that efficiency and clean energy must be priorities globally, and that organizations like Rocky Mountain Institute are critical catalysts, please consider supporting our work or joining our team.

Part 2: RMI Scales Deep Retrofits Through Portfolios and Campuses

Since 2009, RMI’s work to advance deep energy retrofits has focused on a multi-pronged approach to scaling: 1) collaborate with project teammates, owners, and other fast movers who learn from and copy pioneering deep retrofit projects, 2) engage entire portfolios and campuses of buildings to impact more than scattered singular building retrofits, and 3) develop new, better, and more comprehensive ways of assessing risk and value associated with deep green buildings, to drive greater investment by financial decision makers.

Engaging portfolios and campuses and better assessing risk and value are both new and challenging topics, and our donor-funded work to advance them is by no means complete. But we believe we must aggressively accelerate the nature and quality of retrofits of all sorts in most commercial buildings—and it is imperative that we do so in order to rapidly drive down energy use and CO2 impact.

In today’s part two of a three-part series, we take a look at RMI’s work on portfolios and campuses. (Read parts one and three.)

Portfolios and Campuses

Deep energy retrofits are not for every building, and cannot be efficiently or economically done at random. Our portfolio and campus work—a significant thrust for four years now—has been revealing insights into this area and helping major players shape plans, standards, and processes. We have continually moved the bar higher on expectations for energy savings in a well-run portfolio or campus of buildings, especially when taken as a whole. Universities and corporate campuses are now leading the way toward zero carbon emissions—in fact, they can be re-envisioned as renewably powered microgrids.

Car Dealerships

Shortly after we wrapped up our work on the iconic Empire State Building, we began another influential—if less sexy—project focused on car dealerships. These are small buildings, not very valuable or appealing, metaphorical islands in seas of parked cars under powerful lights.

Working with Ford Motor Company and a big energy services company (ESCO), we selected three dealership facilities and executed our standard deep energy retrofit diagnosis and whole-system design effort. The resulting build-outs saved 60–80 percent of the energy with good economics. Despite three different geographies, RMI identified a common package of energy-saving measures focused on indoor and outdoor lighting, mechanical controls, commissioning, weatherization (plugging leaks), and when-it-fails HVAC equipment upgrades. This package saved the vast majority of the energy and could be scaled up—a lot.

There are currently more than 17,500 new-car dealers with total energy use exceeding 50 trillion BTU/year. Only a handful have been upgraded for energy efficiency. Many ESCOs and several financing players have discussed this opportunity with us, and some players have recently begun their own rollout of dealership retrofits complete with financing options, all taking advantage of relatively short paybacks available because of the heavy role lighting plays in the car sales business. The ball is rolling, though it could use a big push.

Malls, Retailers, and Supermarkets

Car dealerships represented a huge portfolio of reasonably similar buildings, but they comprised a portfolio with many (many!) owners. What about other large portfolios, but with fewer owners?

We realized that retailers and the mall owners that housed them presented another opportunity. The largest players in this arena had thousand of buildings, huge energy demands, and well-structured processes for setting standards and driving change. And, we had already worked with two big names: SuperValu, a northeastern supermarket chain, and WalMart, back when it was first beginning to consider what a more energy-efficient store might look like.

We quickly found and executed two more projects with large supermarket chains, Kroger and HEB, where tiny margins make energy savings a very, very big deal. In both cases we helped develop designs—now built and running well—for new test bed stores. These not only formed the new standard for all new stores, but, on a component basis, serve to pre-qualify equipment for retrofits or upgrades. Energy upgrades are one of the most profitable investments available to both store chains, and an RMI speech on the topic at the Food Marketing Institute in 2011 confirmed that these examples and their value are now well understood by the supermarket industry. Finding capital for projects remains a challenge, however.

A Focus on the Owner-Occupant

We then reached out to other retailers and major office building owner-occupants to look into more diverse (and less energy intensive) buildings portfolios. After discussions with many, The Exchange, which runs department stores, quick-service restaurants, and convenience stores on military bases, answered our call. So did Kaiser Permanente, one of the country’s largest and best-regarded health care organizations with a fleet of hundreds of office buildings and dozens of hospitals. As did telecommunications giant AT&T, which boasts a huge portfolio of more than 60,000 structures, courtesy of its Bell System heritage.

In all cases, our scope was research, planning, and limited testing focused on a central question: How to save the most energy from a large set of buildings, over time, with the most compelling economics?

RMI found that AT&T had huge opportunities requiring multiple strategies integrated carefully with workplace upgrades and equipment replacement cycles. Given corporate capital allocation requirements, it was also vital to bundle many projects together to leverage external, efficiency-focused capital to speed impact. At Kaiser, it became clear that efficiency provided a fantastic path toward meeting the company’s goals of a 30 percent absolute reduction in its carbon and energy footprints, but new governance, funding, and other mechanisms had to be created to capture it. Work at The Exchange, still underway, has revealed deep and broad savings opportunities, but economics, even in very similar buildings, vary widely. Project returns are best when linked with equipment upgrade cycles; much poorer when they are not.

These findings are among many that are universally applicable in larger owner-occupied portfolios, including almost all the large retailers like Target, Best Buy, Macy’s, and WalMart, as well as mall owners like Simon Property Group, with which we have built relationships over the last few years. These insights, and other practical advice, are integrated into RMI’s tools sets and frameworks on RetroFit Depot. It is clear that the impact potential in these large portfolios is huge but challenging to plan and capture.

Working with the Nation’s Largest Landlord

In 2010, RMI partnered with the largest and most influential office owner of them all: the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA). Long a real estate leader—and well recognized as such within the industry—the GSA’s 80-million-square-foot portfolio must become net zero by 2030 and three percent more efficient every year, according to Executive Order 13514.

The GSA does not have the capital to do this, however. So RMI has teamed with GSA leadership to define how performance contracting can be optimized, in order to drive broader and deeper retrofits. Rallied by a Deep RetroFit Challenge Summit in Boulder, Colorado, in 2011, energy service companies (ESCOs) have already roughly doubled the amount of savings (39 percent vs. 18 percent) they expect to deliver to GSA, though projects are not yet completed. We expect continued GSA leadership in expanding the potential of ESCOs.

State governments are another institution with significant building portfolios. In a still-evolving effort, we have advised government staff that are shaping, or practitioners serving, no fewer than six states planning or executing energy saving programs in state buildings. For instance, we contributed ideas and experiences to planners designing Governor Cuomo’s New York State program to improve energy efficiency in state buildings 20 percent by 2020. Meanwhile, the contractor supporting Missouri’s highly effective two percent (additional) savings per year program approached RMI to consider how to learn from and expand the Missouri program to other states.

After the 2011 release of Reinventing Fire, our book highlighting the longer-term fossil-fuel-free potential of the U.S. economy, it became clear that “what to do Monday” was a key question, so we executed the first (we hope) of a number of smaller “Reinventing Fires.” This first one was with the state of Connecticut. Connecticut’s leading state building efficiency program became a key part of the resulting 2013 comprehensive energy strategy focusing on efficiency, natural gas, and renewables.

University Campuses

RMI has a long history of studying universities as many are perfect test beds, and properly led, are capable of moving quickly. They have high diversity of buildings, but half or more of the energy use is often centered in three key areas: labs and hospitals, dining facilities, and data centers. All three are areas where RMI has done design work for new facilities, thus providing insights relevant to retrofits.

Some of our early work with campuses set the scene. Our Accelerating Campus Climate Initiative study and book with the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) dug into the challenges and opportunities of setting aggressive climate strategies, and gave us significant insight into the complexities of university campus decision making.

At Penn State, we learned of the vast gulf often present between facilities, research, and teaching in larger universities. At the University of British Columbia, we discovered potential solutions to bridging those gulfs, using very clear and active governance mechanisms. With Appalachian State and the University of North Carolina system, we have learned about the huge differences in campuses within large public university systems, and the benefits from shared learning like the annual UNC Energy Summits we co-host. At the University of Southern California we have learned that with patience, the sources of value and drivers of change can be found even for universities where sustainability and climate are not shaping important agendas. And our long-time links to our local university, the University of Colorado at Boulder, helped us realize that there was a timing opportunity. Many of the key academic buildings in this country were built during a boom time—part of the reaction to Sputnik—in the 1960s and 70s, and now constitute one of the “ripest” sets of buildings for retrofit anywhere.

These all have led to our current, capstone university project: a partnership with Arizona State University and Ameresco to develop an explicit roadmap to deliver a net-zero carbon university by 2025, one of the most aggressive climate commitments from any major university. Initial details of the program were released in October, but results will not be made public until summer 2014 when ASU, Ameresco, and RMI finalize the university’s climate neutrality implementation plan.

RMI has very high hopes and has made initial plans on how to rapidly spread insights from ASU and other leading universities because of a simple fact: universities are not only great test beds; they also shape and execute research. And the research opportunities in the areas of efficiency and renewables are tremendous, as we have found when serving as reviewers for government research grants and as judges for commercial real estate management company CBRE’s recent million-dollar research grant program. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, universities shape the knowledge, attitudes, and careers of their boards, alumni, leaders, students, and staff. They in turn shape the cities and regions in which they live and work. Universities are one of the most powerful leverage points we have in driving energy transformation, and we are launching programs to do just that.

Part 3: RMI Scales Deep Retrofits Through Deep Retrofit Value

Since 2009, RMI’s work to advance deep energy retrofits has focused on a multi-pronged approach to scaling: 1) collaborate with project teammates, owners, and other fast movers who learn from and copy pioneering deep retrofit projects, 2) engage entire portfolios and campuses of buildings to impact more than scattered singular building retrofits, and 3) develop new, better, and more comprehensive ways of assessing risk and value associated with deep green buildings, to drive greater investment by financial decision makers.

Engaging portfolios and campuses and better assessing risk and value are both new and challenging topics, and our donor-funded work to advance them is by no means complete. But we believe we must aggressively accelerate the nature and quality of retrofits of all sorts in most commercial buildings—and it is imperative that we do so in order to rapidly drive down energy use and CO2 impact.

In today’s part three of a three-part series, we take a look at RMI’s work on risk, value, and decision making. (Read parts one and two.)

Risk, Value, and Decision Making

In our earliest work on the Empire State Building and car dealerships, much of the key analysis and decision-making about whether and how to execute was financial. In those efforts, we used relatively simple life-cycle costing models, and since few good ones were available, we built better ones and made them available for all on our website.

But we also realized that life-cycle costing was the tip of the iceberg. If the goal was to dramatically improve the economics of retrofitting existing buildings and driving far more capital into the attractive opportunities that resulted, we had to do a lot more. Reviewing all the levers for improving retrofit economics, it became clear that RMI could add the most significant value in reducing the risk and cost of executing the complex design and build process of a retrofit. With that we set to work.

The Role of Building Energy Modeling

The first step was to develop and host the first-ever workshop for all the leaders of the U.S. building energy modeling (BEM) community. Called the BEM Innovation Summit, this two-day workshop sought ways to capitalize on the biggest opportunities for building energy modeling to support widespread solutions for achieving low-energy buildings. RMI has been involved in advancing how energy modelers can help improve confidence in efficiency investments. Most recently, RMI teamed with two research facilities to demonstrate methods for quantifying uncertainties, and thus risks, of modeled performance estimates.

RMI is also addressing owners’ needs to understand risk, which allows them to manage it. For instance, through DOE-funded work, RMI authored Building Energy Modeling for Owners and Managers, a guide to specifying and securing services. Equally important, these efforts have made RMI a go-to source for key thinking about risk reduction and access to less-expensive capital. In the end, our work on finance is about risk reduction and value increase to enable far more money to flow into making buildings better and more efficient; to “making older buildings even better than new ones.”

With 80 billion square feet of existing commercial buildings, and an ongoing new-build market equaling the best one to two percent of that, this is essential and must happen on a massive scale. We are determined to overcome the nontechnical barriers with the same drive as the technical ones.

Overcoming Split Incentives

Encouraged by a donor who had his own real estate portfolio, RMI teamed up with the influential Building Owners and Managers Association International (BOMA) to develop a practical new report, Working Together for Sustainability: The RMI-BOMA Guide for Landlords and Tenants. The report detailed the conclusions of a workshop on how to overcome the classic split incentive issue, which inhibits owners from making efficiency improvements that a tenant benefits from but will not pay for, and vice versa. Owners, landlords, tenants, and brokers all contributed and detailed ways to work together to overcome this hurdle. The free report has been aggressively and broadly distributed by BOMA and other channels (BOMA is a 100-year-old organization with 114 active branches in the U.S. and Canada) and RMI continues to work with BOMA to get new messages and ideas out today.

Small But Important: Retrofits in Smaller Commercial Buildings

Encouraged by BOMA, and cohosted with the Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance (NEEA), RMI in 2011 also took a first look into the challenges of planning and financing retrofits in smaller commercial buildings, those under 50,000 square feet. This represents the vast majority (90 percent) of all commercial buildings and more than 50 percent of the space in the country. These buildings are considered too small to study extensively, with owners or managers too busy to navigate the complexity of any but the most urgent retrofit projects, much less the challenges of utility rebate and government tax credit paperwork.

The workshop found that 75 percent of these buildings are zombies whose owners cannot afford or have no interest in investing in their upkeep, even though rents, comfort, and longevity would all go up if they did. This is a massive opportunity for cities and local utilities to encourage, and local entrepreneurs to serve, ideally with turnkey solutions. The results have been leveraged in RMI’s community and electricity work and Reinventing Fire projects ever since.

Identifying Comprehensive Deep Retrofit Value

The small buildings Retrofit finance work also provided the final stimulus to look not just at risk and its links to financing, but more broadly at value. Good, deep green buildings such as those resulting from a deep retrofit are more comfortable, productive, marketable, attractive to recruits, supportive of corporate sustainability-linked brands, and many other great things. Many such values are hard to quantify. But since the real estate industry has very well established techniques for handling other hard to quantify but still vital factors—such as location, or marble lobbies, or fast elevators—why not get these value drivers into the decisions? Everyone would be better served if we did: owners, brokers, tenants, and the planet.

Scott Muldavin, who literally wrote the book on this topic, joined RMI in 2011 to help us and now serves as an advisor and collaborator. Our RetroFit Value Model, in a first version aimed at owner-occupants (half of the market), is due out in January 2014. Thoroughly reviewed and very well received by those in the field of sustainability and real estate finance, it lays out the logic, research, insight, and clear methodologies for capturing all the value components of a highly efficient building, to enable better and wiser deals to be made. RMI is of course using the framework in its own real estate planning. And we plan to share the work broadly with the help of friends like Urban Land Institute, BOMA, CoreNet Global, and many others. We also hope to find support to expand this approach to investors and brokers and specialty markets like universities and the GSA, where the tools will need some adjustment.

We are by no means done with the process of driving more capital, more portfolio strategy, and more aggressive campus goals and progress into the U.S. energy system. The stakes are huge and the timing is critical. Without strong savings in buildings, U.S. electricity and gas use will continue to grow, and new, long-lasting but regrettable investments in fossil-fueled electricity and natural gas distribution systems will be made. Those would be investments we do not need, because less money can bring permanent savings via efficiency, with no inflation or risk. Such fossil-fuel investments would likewise be ones the planet cannot afford, because the unnecessary electric plant WOULD of course be used, to the detriment of all who could have been richer, more comfortable, and more productive without it.